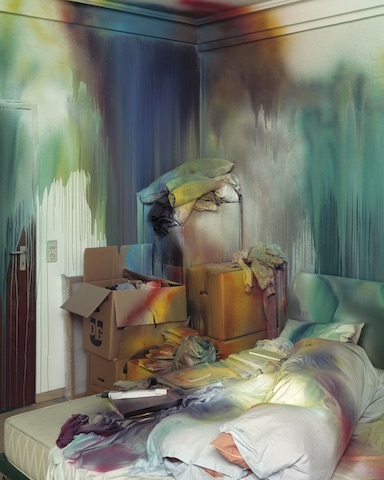

Katharina Grosse is a painter and iconoclast. From 2010 until earlier this year she was professor of painting at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, but is recognised within the wider artworld for pushing painting beyond its traditional definition as a discrete medium confined to a frame. In her works, paint is applied (using a spraygun) as abstract explosions of colour or as stencilled imprints, to all aspects of space and to the extent that Grosse’s work might be described as sculpture, installation and, to a certain degree, interior and exterior architecture (in a series of untitled works on the facades and interiors of corporate headquarters, university buildings and infrastructure hubs). So much for the order of things. On the one hand, Grosse works in her Berlin studio spreading acrylic paint over canvases; on the other, she goes beyond the atelier to spray it over bedrooms (Das Bett (Bed), 2004), over the structures and landscape of abandoned military bases (Rockaway!, 2016) and even over national coastlines (as is the case with Asphalt Air and Hair, 2017, in Aarhus, Denmark). She’s part of a tradition and apart from it at one and the same time.

Everyone knows that painting, as it is understood through the history of Western art, was invented sometime around 650 BCE, thanks to an anecdote famously reported by Pliny the Elder (in his Natural History, 77 CE), in which he describes how Kora of Sicyon traced the outline of her lover’s shadow on a wall shortly before he left for battle. Painting was invented by a woman as an expression of love. Shortly afterwards, her father, Butades of Sicyon, who made clay tiles for a living, modelled the outline in clay, inventing moulded sculpture and subsequently a new business of moulded tiles. A man then turned it into a commodity and initiated the art market.

The wall was destroyed by fire around 200 years after Kora left her mark on it. And Butades’s relief sculpture vanished in 146 BCE, when Lucius Mummius destroyed the entire city of Corinth (where Butades and Kora had lived) during the Achean War. So we have to take Pliny’s word for it when it comes to all the inventing stuff. And as Pliny wasn’t really into dates, we have to accept that ‘around 650 BCE’ falls somewhat shy of being a fact and is rather the product of later guesswork by historians. Pliny wasn’t really familiar with cave paintings either, which were the kind of thing that later works such as E.H. Gombrich’s The Story of Art (1950), in which the Austrian invents art history, used to put at the beginning of their histories of painting. Moreover, earlier this year a group of scientists who subjected the carbon crusts of a number of cave paintings to uranium-thorium dating suggested that painting wasn’t even invented by Homo sapiens at all. Rather, Neanderthals may have painted symbols in caves in Spain more than 64,000 years ago: that’s 20,000 years before prototypical modern humans even bothered to show up in Western Europe. Pfff… This is art and we shouldn’t let an article published in a magazine titled Science (23 February 2018) get in the way of a romantic tale.

Grosse herself is no stranger to the romantic origin story. Talking to Emily Wasik in Interview magazine back in 2014, the artist described the origins of her own drive to make art: ‘As a child, I would play a game with myself where before I got up, I had to first erase the shadows on the wall. I invented an invisible paintbrush to paint over the shadows of the windowsill or the lamp or whatever was there. It became like an obsession.’ Intriguingly, and perhaps typically, while there’s an echo here of Pliny’s originary tale, Grosse locates her own artistic beginnings as being rooted in erasing the very thing that Kora sought to preserve.

This month, Grosse brings her work to the Chi K11 Art Museum in Shanghai, a city in which she lived while her father was teaching at Tongji University in 1981. There she will explore some of the myths about painting’s beginnings and ends via a largescale installation split into five sections, or episodes (the journey takes place over time as well as space), titled Mumbling Mud, which both conjures the origins of pigments and the use to which painters put them, and the Cantonese expression for mumbling or slurring, gwai sik nai, which literally translates as ‘a ghost eating mud’.

The first section, ‘Underground’, consists of messy piles of accumulated soil and building materials that have been spraypainted by the artist, a wasteland that is also a site of creative potential, that suggests a dialogue between the building blocks of painting and of the city. The second, ‘Silk Studio’, deploys curtains of silk printed with images of Grosse’s studio complete with works in progress. The third, ‘Ghost’, comprises a large, skeletal, white Styrofoam sculpture that looks – from the model version at least – like a structure from the set of Alien (1979) or The Predator (1987), or perhaps like a scholar’s rock incarnated from an early Chinese painting, or like a splash of paint captured midflight. Or, maybe truer still, it is a blank object onto which audiences will project their own colourful narratives. ‘Stomach’ is a colonic labyrinth of hundreds of metres of white fabric, hung from the ceiling and sprayed with Grosse’s signature bright colours in such a way that its folds and undulations are highlighted and viewers sucked in. Whether visitors are consuming art in this Gesamtkunstwerk, or whether art is consuming its viewers, remains to be seen. The final stage of the journey, ‘Showroom’, comprises a set of living-room furniture (complete with the image of a stacked bookcase, a reminder perhaps of the links between Chinese painting and calligraphy, of painting as a space of signs and symbols) over which Grosse has sprayed paint in a manner that recalls the disruptive and vandalistic nature of graffiti: art projected over life in a scene of order and disorder that equally acknowledges the fact that the K11 galleries are located in a shopping mall, and that it is to this environment that the viewer is about to be returned. And that art is at once apart from and a part of contemporary consumer culture. From Kora to Butades in five easy steps. But then again, China’s painting traditions are thought to have been developed around two centuries before those of Pliny and the West.

Mumbling Mud is on show at the Chi K11 Art Museum, Shanghai, through 24 February

From the Winter 2018 issue of ArtReview Asia