The late filmmaker’s work asked whether institutions can leave room for human compassion and dignity – and presented an antidote to our messy, distracted times

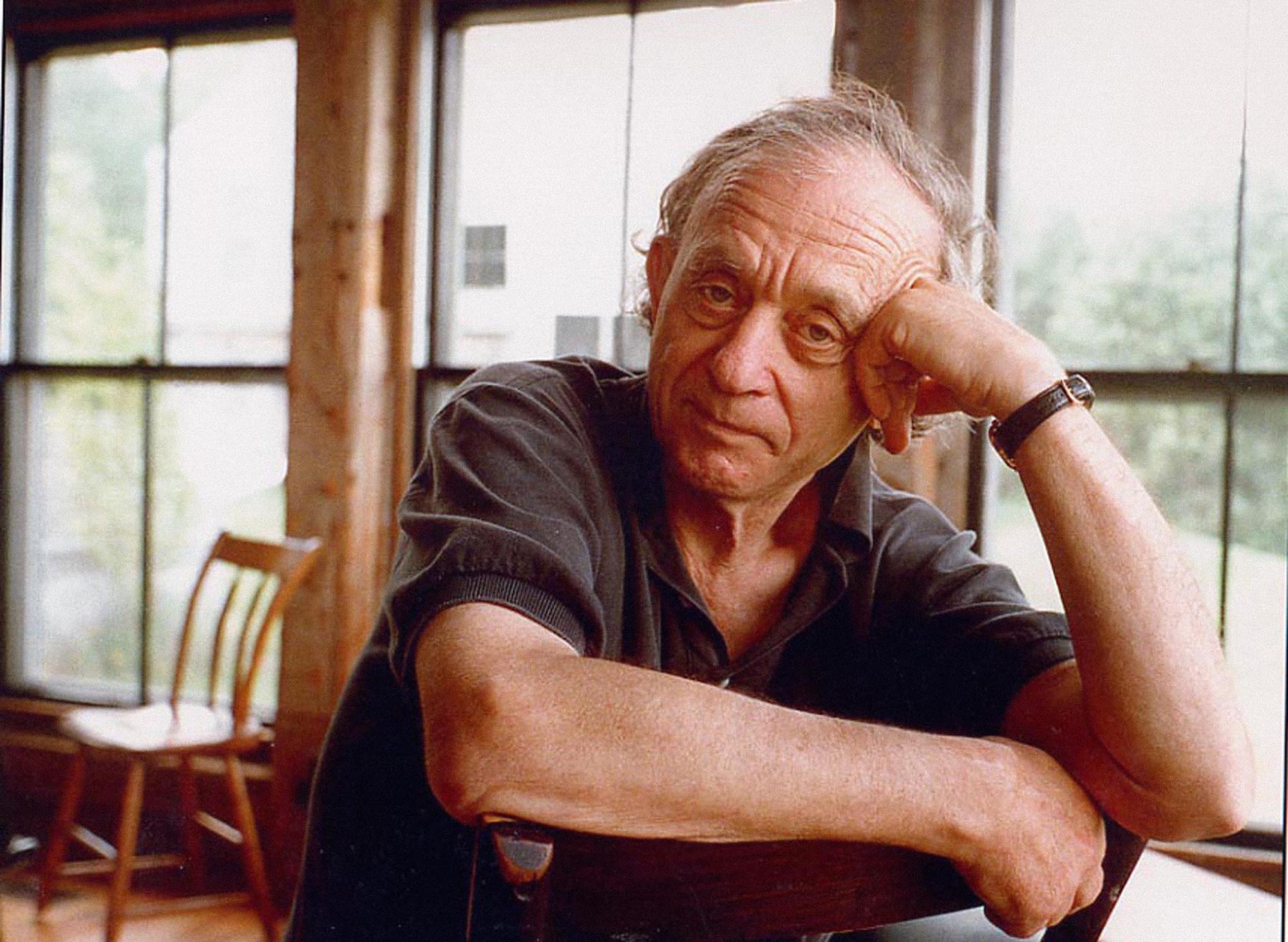

Frederick Wiseman, as he was keen to point out, did not make documentaries. His films, which he called ‘reality fictions’, had few of the stylistic conventions we’ve come to expect from documentary cinema: no narration, no interviews, no music, no cutaways explaining the history of the topic. Wiseman, who died this week aged 96, threw his audience into a location and trusted they would find their own way through. But all of his films, whether they were filmed in a military facility, Berkeley campus or a Miami zoo, shared something in common: they all slowly revealed how power operates.

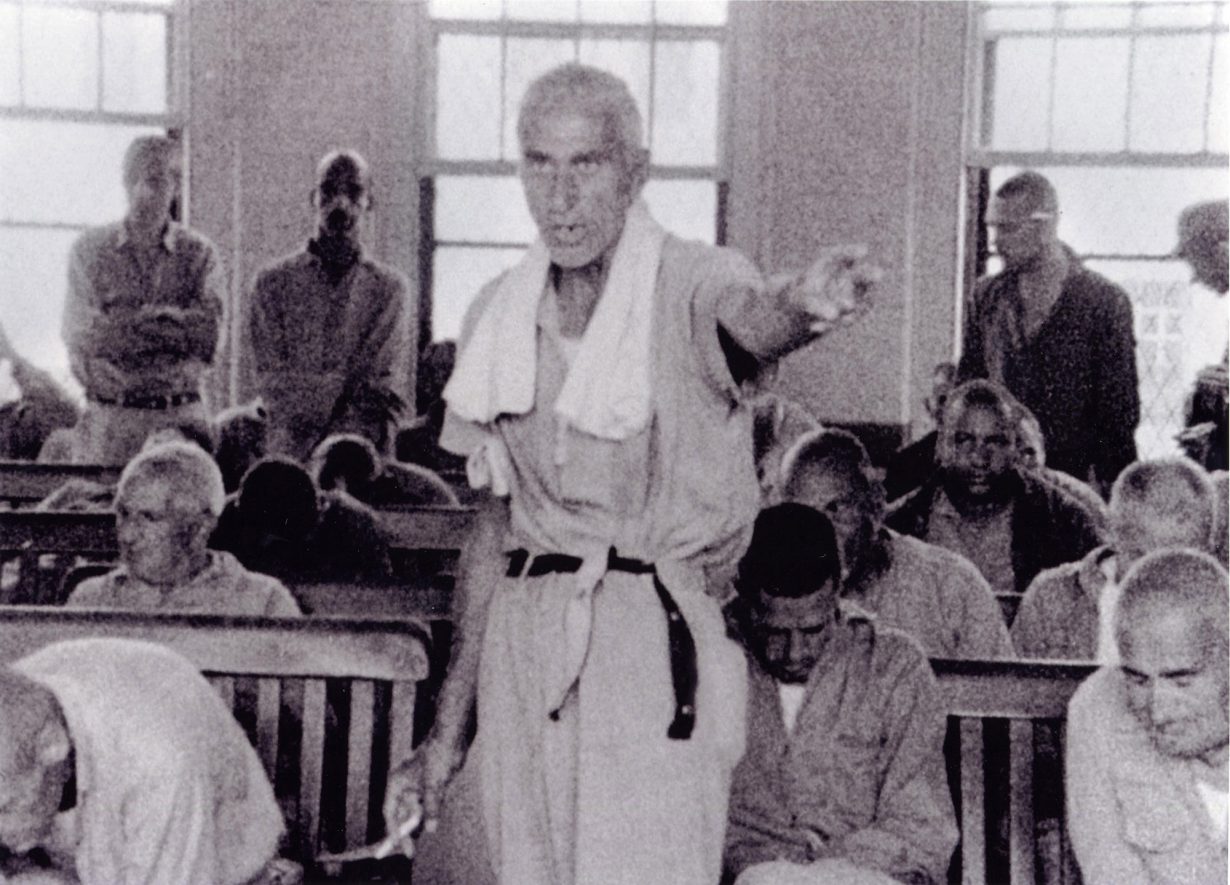

Foucault wrote that power was everywhere. Rather than being something purely top-down and sovereign, Foucault argued that power was dispersed and enacted through everyday institutions: mental hospitals, schools, the church – all of which were subjects of Wiseman’s films. From his earliest feature, Titicut Follies (1967), set in the Bridgewater State Hospital for the Criminally Insane, to his last, Menus-Plaisirs – Les Troisgros (2023), about a three-Michelin-star restaurant in Ouches, France, Wiseman documented how power performs within organisations. But while Foucault wrote in convoluted, often impenetrable, sentences, Wiseman’s cinematic language was deceptively simple: long, unbroken takes, with no ostensible directorial interference. This stripped-back style of filmmaking, however, created the conditions for institutions to, in effect, indict themselves.

In Welfare (1975), one of Wiseman’s best films, there are repeated moments of desperation as both staff and the public struggle within the benefit system’s regulatory labyrinth. The film’s most memorable moments portray claimants, many of whom are Black, speaking to white employees, growing increasingly frustrated as they are sent away and told their troubles are someone else’s responsibility. At its heart, Welfare is a film about people trying to get someone with authority to listen to them. The film’s bureaucratic maze has been likened to Kafka, but Welfare ends with a man, with ten cents to his name, citing Beckett. “I’ve been waiting for the last 124 days, since I got out of the hospital,” he says. “Waiting for something. Godot? You know what happened in the story of Godot? He never came. That’s what I’m waiting for, something that will never come.”

For Foucault, people internalised rules through norms, becoming ‘docile bodies’ that learn not to resist. This starts at the earliest institutional level, the school. In High School (1968), Wiseman’s second feature, bodies are judged, sexuality is policed and expression is restricted. The film ends with the school principal reading a letter from an ex-pupil fighting in Vietnam. “Don’t worry about me,” she reads aloud. “I am only a body doing a job.” By ending the film with this moment, Wiseman’s message is clear: conformity will lead you to the grave, and before you go, you may even write back to your school to say thank you.

There are plenty of moments in Wiseman’s films that are difficult to watch. In Titicut Follies, naked prisoners are berated and humiliated by doctors and security guards. A scene of force-feeding is among Wiseman’s most notorious. (The film was banned by Massachusetts’s state courts for 24 years.) In Law & Order (1969), a white police officer strangles a Black woman accused of prostitution during an arrest. Moments like these prove Wiseman’s theory, as he stated in interviews, that people do not really change their behaviour in front of a camera. We may think that in the era of smartphones, social media and cancellation, individuals are more wary of public shame and professional punishment. We need only think of the videos of George Floyd, from 2020, and Renée Good, from January this year, to be proven otherwise.

Looking at his filmography chronologically, one might get the impression that Wiseman gradually depoliticised as he grew older. After the confrontational urgency of his earlier work, his later films were set in, among other places, Manhattan’s Central Park, the American Ballet Theatre, London’s National Gallery and the Paris Opera Ballet. While they lack Titicut Follies’s sadism or Law & Order’s brutality, they nevertheless depict embodiments of power, showing how it operates within cultural institutions and how it is claimed in public spaces. In Central Park (1990), as well as capturing joggers and opera performances, Wiseman filmed the many homeless people who slept in the park, and the policemen who moved them along. A moving sequence of visitors walking among the AIDS quilt, as names of the dead are read aloud by activists, emphasised how public space can be a site of mourning and healing.

One of his last films, Ex Libris, a 200-minute film about the New York Public Library from 2017, showed how libraries serve as both bastions of knowledge as well as spaces for community dialogue. Throughout the film, we see members of the public search for historical information about history or a particular issue that the internet can’t provide. During Trump’s first term, these ideas took on a radical quality. In an interview during the New Yorker Festival, Wiseman said that Trump ‘made’ Ex Libris political: “the library represents everything that he’s against and doesn’t understand: science, education, learning, the role of immigrants in American society, diversity, openness, culture.” National libraries are both windows and sentries to the truth. As Trump 2.0 interferes with universities and museums in an attempt to rewrite history, the political overtones of Ex Libris have only grown stronger.

Wiseman’s films are known for their long running times. His longest, Near Death (1989), about terminally-ill patients at Boston’s Beth Israel Hospital, is ten minutes short of six hours. His films demand attention and perseverance, not exactly abundant qualities in the age of double-screens and brainrot. But what feels like endurance is in fact empowerment. Wiseman asks of his viewers qualities that are necessary but under threat in democracy: patience, consideration, independent judgement and critical thinking. With no voiceovers or title cards, we have to situate ourselves and come to our own conclusions.

That said, Wiseman never claimed to be just a passive observer. One of the reasons he hated terms like cinéma vérité or ‘fly-on-the-wall’ is because they imply an absence of agency from the filmmaker. (‘I like to think I’m somewhat more conscious than a fly,’ he once said.) While his films ran to several hours, Wiseman shot hundreds of hours more that never made the cut. It was the editing process, he claimed, that determined the theme of a film, more than the filming.

Across his career, Wiseman repeatedly returned to the question of whether institutions can leave room for human compassion and dignity. Among the scenes of structural inequality and violence, Wiseman shot hundreds of examples of ordinary people trying to make a difference within obtuse systems: doctors, nurses, social workers, librarians and community members. Wiseman was as fascinated with the people who upheld bureaucracies as the bureaucracies themselves . In Jackson Heights (2015), for example, celebrates the diversity of New York City’s Queens neighbourhood: ahead of an upcoming LGBTQ pride parade, Council member Daniel Dromm addresses a local crowd, celebrating the “167 different languages” spoken in the neighbourhood, and proclaims that LGBT visibility is woven into the fabric of the Jackson Heights community. Throughout In Jackson Heights, Wiseman films community organisers and local NGO workers who help connect disparate immigrant populations into civil society. They try to foster a sense of community.

More than any other filmmaker, Wiseman showed us how authority is performed through institutions, the bureaucracy they create and protect and how it spills into public space. Wiseman wanted us to look and to listen. Like Foucault, he knew that power is everywhere. If we learn to look, we might begin to see it ourselves.

Read next An Ode To Béla Tarr