Maybe it’s normal that pop culture should become museum culture, since a lot of pop culture is now getting very old

As Taylor Swift sweeps through the UK, on her vast, record-breaking Eras world tour, the sheer mass, devotion and spending power of Swifties has altered the economic fortunes of the cities in which she alights. The prospect makes every politician a Swiftie: London’s mayor Sadiq Khan enthused that Eras would generate £300m of extra revenue for the capital. So, might the pop deity have a similar effect on the fortunes of art galleries? London’s Victoria & Albert Museum (V&A) is about to find out, as this week it opens Taylor Swift | Songbook Trail, a cannily timed ‘journey’ through the museum’s galleries with displays of 16 ‘looks’ worn by the singer through her near two-decade career – costumes and accessories will be displayed alongside instruments, music awards, storyboards and archive material. What with Swift returning to London for five more dates in August, the V&A is no doubt hoping some of those 500,000 Swifties will stop in before heading to Wembley Stadium in their fluffy, pink Stetsons.

It may be a piece of summer-season fun, but the V&A’s leap onto the Swift bandwagon points to changes in UK museum culture as big venues contend with the need to supplant their traditional, ageing audience with new, younger attendees. Indeed, many big institutions are still getting over the effects of the COVID lockdowns, which saw public galleries everywhere shuttered for months, the aftershocks of which have badly disrupted their finances. Exhibitions appealing to younger demographics, especially those that can capture the so-far elusive tween-to-twentysomething bracket, are irresistible to institutions, who are more than happy to court brand collaborations if it will allow access to the cultural tastes of younger age groups: if Barbie the movie was the cinema hit of last summer, then Barbie®: The Exhibition, recently opened at London’s Design Museum, might tap into gen-Z’s love-hate not-quite-ironic relationship with this fading avatar of heterosexist normativity, bolstered by the happy partnership with Barbie’s owner, Mattel. Earlier in the year, kawaii corporate behemoth Sanrio was the headline sponsor of Somerset House’s Cute. Billed as a ‘major exhibition exploring the irresistible force of cuteness in contemporary culture’, Cute similarly managed to cross-capture kids who just wanted to go and see Hello Kitty, their parents who had to take them there and could ponder the cultural histories of cute (from Victorian cat photography to prewar romantic manga), and a section of millennials for whom cuteness seems now to root their more ambiguous attitudes towards gender, adulthood and growing up. In this, Cute was most awkward when it appeared to present genderqueer art (artists included Juliana Huxtable and Sin Wai Kin) as the inevitable outcome of a cultural product essentially created to satisfy the changing sentimental attachments of preteen girls.

In one sense, though, it’s normal that pop culture should become museum culture, since a lot of pop culture is now getting very old, and yet, due to the omniscient archive of the internet, never really goes away: Barbie was born in 1959, Hello Kitty in 1973. In 2014 Taylor Swift made an album titled 1989, her birth year, the album itself a rebooting of her musical profile, achieved by reviving the 80s synthpop sound that her millennial generation had itself never lived through, but wanted to look back to. (80s throwback Stranger Things, for example, debuted in 2016.) Since any bit of our cultural history can be preserved and retrieved, periodically, so that the past is now more constantly accessed than the present, the museum begins to reflect this two-way culture, and the growing interest in past pop culture, its merging with current tastes.

But as pressures to reinvent their audience-base come to bear, and the museum’s relationship to the idea of preserving history becomes more attentive to the collective significance of mass culture (rather than ‘elite’ culture), museums can lapse easily into a mix of fan-indulgence, celebrity sycophancy, brand sponsorship and product placement: late last year you could see pop legend Paul McCartney’s so-so photographs of his Beatles years, at the National Portrait Gallery. And at the V&A, if you can’t wait for Taylor, there’s currently NAOMI: In Fashion, which draws ‘upon Campbell’s own extensive wardrobe of haute couture and ready-to-wear ensembles from key moments in her career’, supported by BOSS (which is, as it happens, ‘collaborating’ on Campbell’s latest clothing line). What remains of the museum’s old function of authorising the high-cultural canon now gets redirected to validate the aristocracy of pop.

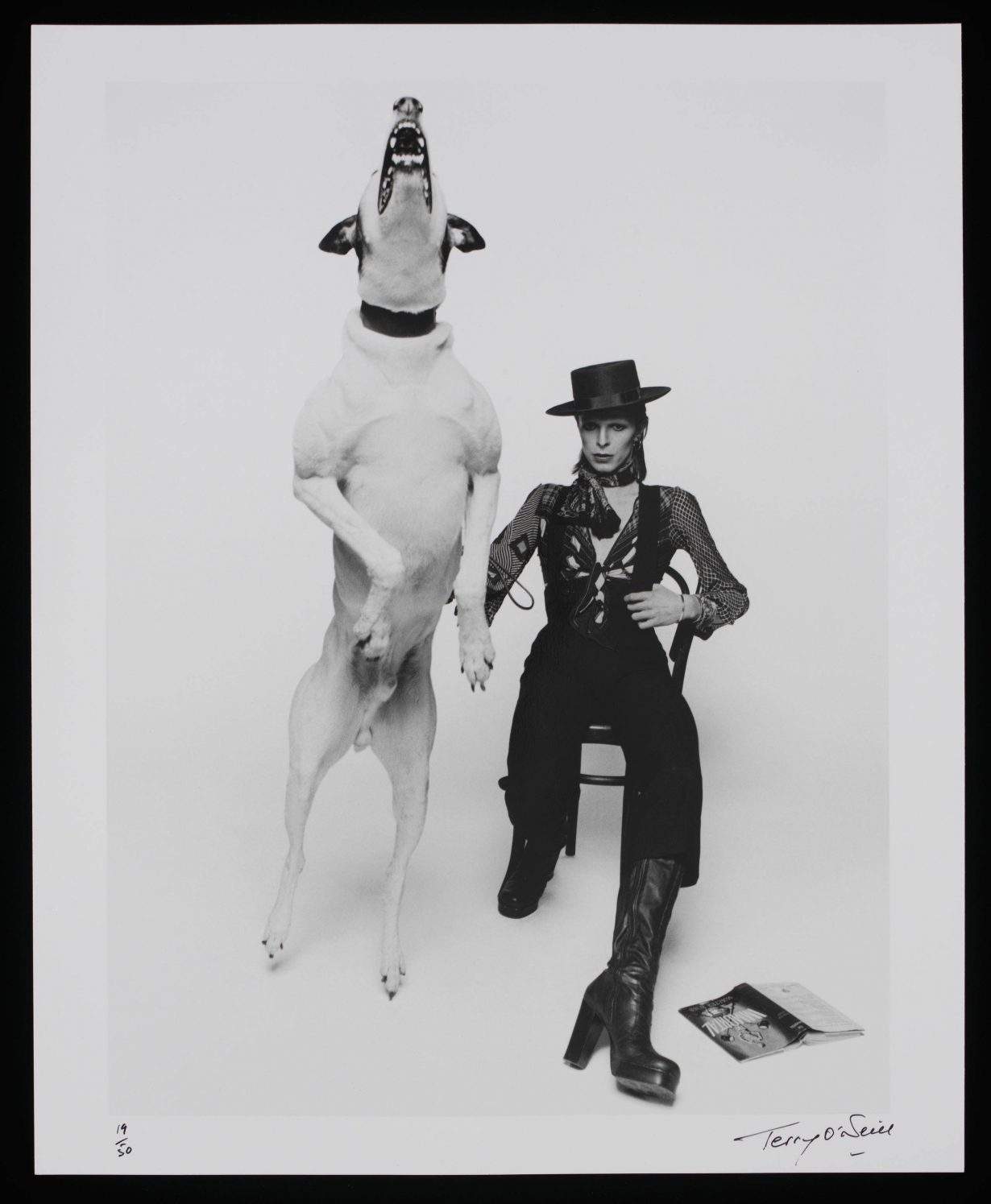

The V&A is of course a natural place to present contemporary fashion, as is the Design Museum for industrial products, while other museums and public galleries find ways to hybridise the popular appeal of fashion into what would otherwise be straight art-history shows, such as Tate Britain’s just-closed Sargent and Fashion. After all, the curatorial embrace of pop in the UK was trailblazed by the V&A, with its 2013 David Bowie Is, a multimedia show of costume, video and photography charting Bowie’s chameleonic pop-star persona through the decades. The opening day of David Bowie Is was the fastest-selling for a V&A exhibition, the subsequent tour of which went on to attract 1.5m visitors over eight venues. In 2023 the museum acquired Bowie’s archive of 80,000 items and a major permanent display based on it will become a key element of the V&A’s new East London building the Storehouse, set to open in 2025.

The V&A’s Bowie project is emblematic of how pop culture is venerated in museums in a way that ‘fine’ art might have been a century ago. Everyone loves Bowie, and everyone loves Taylor Swift, and perhaps nobody cares so much for visual art, or carefully curated exhibitions with thoughtful critical thematics about ponderous issues like colonial legacies or environmental catastrophe. But without a doubt this trend has been accelerated by aftershocks of the pandemic lockdowns, seen particularly in the decline in UK visitor numbers, with many of the top London venues not yet returned to the footfalls of the pre-pandemic: in 2023 Tate Modern saw 1.4m fewer visits than its 2019 high of 6m, while Tate Britain seems to have imploded, managing just over 1m visitors in 2023 (its second worst year, after 2016, since 2004), even with the launch of its major rehang in May.

The V&A itself, having seen close to 4m visitors in 2019, saw a drop of over 800,000 in 2023. Thousands of Swifties eager to touch (or at least see up close) the hems of the Sparkly One would be a welcome boost. Unlike the Eras tour, Songbook Trail is free, the hope being that getting the fan-demographic through the doors might draw in a group who would not usually head for a museum. As museums deal with the shifting demographics of ageing audiences and changing tastes, remaining ‘relevant’ or ‘accessible’ to a younger audience which tends to visit museums less becomes an economic necessity. But maybe that necessity is a good thing, encouraging museums to put on shows of things people actually want to see. Or, by contrast, it might be another sign of how museums, which don’t at the moment seem too clear what they’re supposed to be for, are happy to become an adjunct of entertainment, brands, pop idols and their adoring fans, at the cost of whatever critical distance museums might still have. After all, you’d better not say anything bad about Taylor, or half a million teenage girls might burn your museum down. Heart-hands emoji.