‘I’ve always identified as somebody who has a very thin outer membrane’. The filmmaker, photographer and musician talks to Ross Simonini about truth, sensitivity and watching horror films in lockdown

I spoke to Farah Al Qasimi a week into her coronavirus quarantine in New York City this spring. As she has asthma, she had begun her personal lockdown earlier than most and had spent that time recording an album in her bathroom. Al Qasimi is best known as a photographer and filmmaker, but she is also a musician, singing in punk bands, playing classical piano, writing schoolyard chants and composing synth-heavy film scores. She recently composed the music for her 2019 horror-comedy film, Um Al Naar (Mother of Fire), which is part fiction and part documentary, and investigates the mythological trickster spirits called jinn.

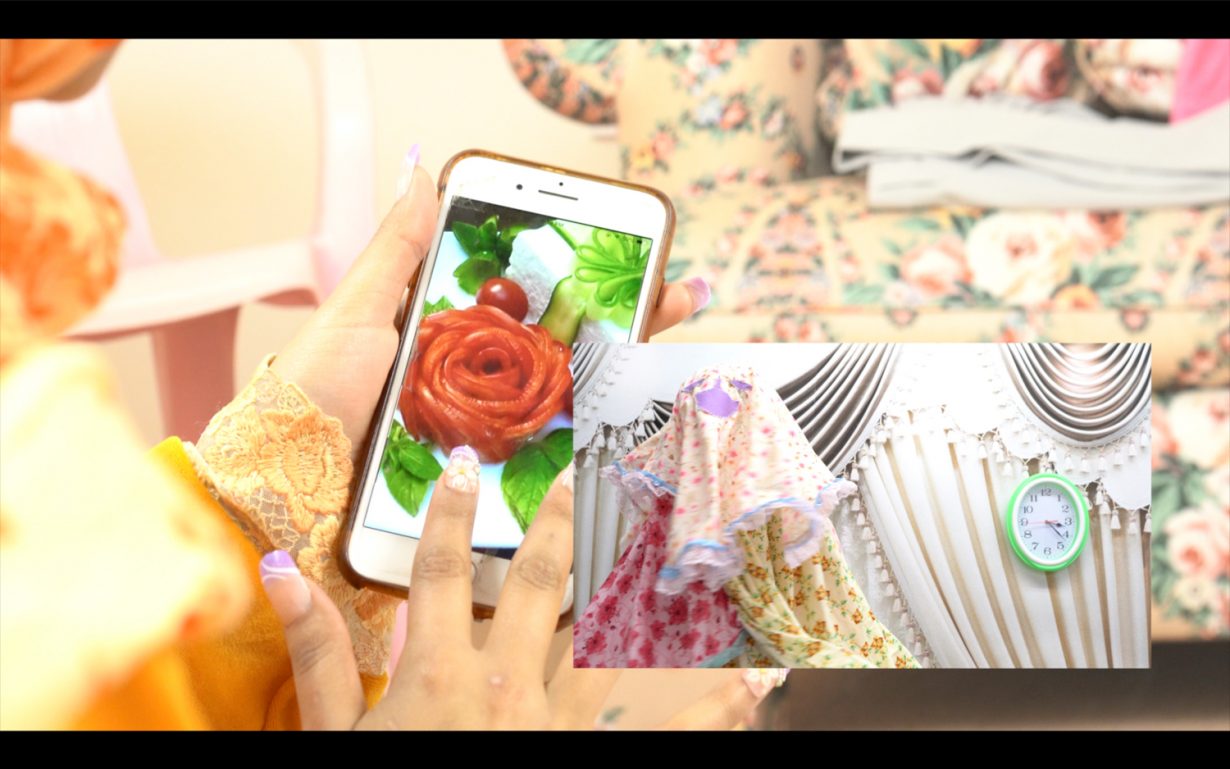

I first encountered her work two years ago, at her first solo show in New York, a collection of photographs at Helena Anrather. It depicted a contemporary, hypermasculine, Middle Eastern culture: guns, meat and beards. (In contrast, she has also documented salons, beauty pageants and malls.) To my eye, many of her images function like paintings: textural and pop-vibrant. Others come together like collages, being meticulous compositions of hyperreal colours and constellations of patterns. The work is pure optical pleasure.

Al Qasimi was born in 1991 in Abu Dhabi and raised there for her childhood, but she has spent much of her life in the United States. Her photos often depict the intersection of these two cultures. At the time we spoke, her work was featured on bus stops across New York City as a part of her project with Public Art Fund, Back and Forth Disco. This seemed to be her way of juxtaposing her two sensibilities: the startling and glittering Emirati aesthetic cast against the grey urban palette of New York’s sidewalks. These photographs remained up for several months during the lockdown and they served the public well, offering glimpses of exuberance amidst the culturally barren streets of the pandemic.

Ross Simonini What films are you watching during lockdown?

Farah Al Qasimi Lots of John Carpenter and horror B-movies. I watched The Thing last week, which is one of my favourites. I’m obsessed with horror, especially as a cure for anxious feelings. A couple of years ago, there was a lot of Daesh activity in the Arab world and I was having nightmares about them every night. I started watching horror movies as an experiment, to see if it would counteract the nightmares. It’s been an addiction ever since.

RS For you, does horror only purge fear, or does it also cultivate it?

FAQ I have thought a lot about this. I have anxiety and depression, and occasional panic attacks and nightmare spells. And the theory I’ve arrived at is: as long as the source of horror in the film is separate enough from your own real-life horror, then you’re fine. For example: my brother made me watch Contagion a couple of weeks ago, and that was a huge mistake, because it was a fictional manifestation of our current reality, and it only amplified my fear. So I tend to gravitate towards supernatural films. Ghosts make me feel more comfortable.

RS Is the same true of horror fiction?

FAQ It’s funny, because I keep thinking about Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower series, which I read a year ago. I had such a feeling of dread when reading it, maybe even anticipation. Now I realise that’s because I was reading a premonition.

Courtesy the artist, The Third Line, Dubai, and Helena Anrather, New York

RS You made a film recently that is considered, in some ways, horror. Does it operate in the same way as these books and films?

FAQ I would classify it in the same genre as poorly filmed clips of ghost encounters on YouTube. You’re watching something, but you’re not completely sure how to categorise it. The film is part documentary, part fictionalised and comedic art piece. The premise of it is a reality show about a jinn, or Islamic spirit, who is complaining about the state of affairs in the Emirates since modernisation.

A lot of the reactions that I’ve had to the film are questions: what parts of it are real? What should I believe? And there shouldn’t be an answer to that. I like tiptoeing that line between documentary and fiction; I think there’s so much of the world that is in it, unedited. For example, I was in conversation with people about their very real experiences with the paranormal. It has always been a part of our culture – believing in the spiritual world, communing with the dead for exorcisms – but as the country strives to modernise, it’s abandoning all of these older forms of knowledge, healing and faith. Exorcisms have recently been outlawed. So I had to go through all of these weird channels to meet one of the characters, Ahmed, who is still a working exorcist – and I asked him questions about the process. He allowed me to record his voice and his hands, but not his face.

RS Do you believe in the supernatural?

FAQ Yeah. Not in a sense that I’ve seen a ghost, but I’ve certainly sensed hostile energies. My family is from the northernmost Emirate, Ras al-Khaimah, and it used to be a burgeoning maritime fishery. And we live on the edge of an abandoned town that is said to be haunted. It’s called Jazirat Al Hamra, we’re right on the border, and I’ve definitely heard noises in our house and felt a presence. I’ve also had sleep paralysis, which a lot of people will describe as being haunted, possessed or crushed by a ghost.

I’m sure you could scientifically explain most paranormal events, but I like to believe that the world is endlessly complex, and that there are different kinds of knowledge. And I don’t believe in the total supremacy of Western medicine. I’m not that distant from my Dad’s generation, you know, who thought that letting blood or burning the back of your neck would fix a fever.

RS Was the jinn mythos a part of your youth?

FAQ Definitely. It was mostly used to design fables. One of them is Umm Al Dowais – she’s a jinn that will seduce you. And if you’re weak, and go into the desert with her, she’ll kill you. She has a sickle for a hand and a donkey leg, in the version I’ve heard. There are different ideas around the jinn, but a lot of people still heavily believe in their existence. Like I said, these exorcisms still happen, even though they have to happen in secret.

RS Was it effective for scaring you?

FAQ Um, yeah. My grandma had some scary stories. One time she was walking home and there was a herd of camels walking alongside her. Then she looked up, and all of a sudden the camels had no heads. But I was also scared of one of the bad guys from Power Rangers, who looked like he was made out of mahshi – a stuffed cabbage my mom used to make me eat – and I used to have nightmares that he’d come out of my closet every night. I was a delicate kid with a robust imagination. But as an adult I’ve been more interested in seeking out experiences with the supernatural, because I have this need to know what else is out there that I’m not experiencing, that I can’t see. A lot of the time, when we hear ghost stories, they’re several degrees removed from us, so for the film I was trying as much as possible to really seek out people who had had things happen to them or who really embody a strong belief in the supernatural.

Courtesy the artist, The Third Line, Dubai, and Helena Anrather, New York

RS Being an artist requires a strong imagination, which is often seen as a benefit, but if the mind flips to fear, that same tool can be weaponised in the service of fear, or anxiety, or depression.

FAQ Yeah, I’m somebody who is very sensitive and that’s often a word that’s used negatively. I’ve always identified as somebody who has a very thin outer membrane. I’m heavily affected by whatever environment I’m in. I think that it is what makes me a curious person, and an incredibly anxious one.

RS Are you interested in using your art to scare people?

FAQ I’ve tried. I’m always curious about what elicits a response, especially as somebody who really loves movies, the whole combo of storytelling, music, effects, visuals and acting. I’m interested in how you use those tools to make people feel. I think that with each thing I make, I get a little bit closer to understanding that. I mean, I think it’s impossible. There’s always going to be a broken telephone game between what you imagine the work does and what it actually does when it’s out in the world. A couple of people said that they cried in the film, which made me really happy, because I think that they were crying for the right reasons.

A helpful rubric for me is testing whether kids like it. I will try and find a kid within reasonable age, usually my nieces, and show them the work, especially if it’s a video, and if there’s interest, then I’ve succeeded. I don’t aspire to make work that is overly self-referential or didactic, and that can’t be experienced or understood by everyone.

I appreciate a lot of work that doesn’t operate within those boundaries, but for me it’s important. I mean, even thinking about humour and how to make people laugh, with horror, there’s a jump scare and then there’s a slow build, and with comedy, there’s the fart joke and there’s the knock-knock or situational joke. And I like to unlock some of those things through the work, rather than just intellectual interests. I like having fundamental experiences that are across the human experience.

RS Fear brings us back to the childlike vulnerability of wonder.

FAQ Exactly.

Courtesy the artist, The Third Line, Dubai, and Helena Anrather, New York

RS Do you get much pushback about your looseness towards truth in your work?

FAQ I think a lot of the photo community gets really bothered by it, and it’s kind of funny, but there’s been this longstanding intellectual tiff between the photography community with a capital P and the art community around the importance of truth. [People] like to control what they know. I think it’s a very human thing, but it doesn’t always serve us in the best of ways.

RS What do you think about the old idea that photography steals the soul of the subject?

FAQ That makes me think of this Susan Sontag quote, from On Photography, where she compares the lens to a gun and talks about photography being an inherently violent act in which you’re taking something from someone. I mean, I’m extremely sensitive about the way that I get photographed. I can’t tell you how many times somebody will tag me in a photograph on Instagram and, you know, my face is not looking the right way or I have a double chin or whatever, and it just gives me the worst anxiety. And then I think: wait a minute, nobody cares. When I photograph people, I will always get their approval before they are shared.

RS Does your photography cross over with the paranormal, too?

FAQ Definitely.

RS I’m down here in Florida and there’s this place nearby called the Skunk Ape Headquarters, which chronicles one of these cryptozoological animals.

FAQ Oh yeah. I know all about the Skunk Ape.

RS So you’ve probably seen these vaguely Bigfoot-like photos of a fuzzy figure in the distance. Now, in the age when everyone has a smartphone, it’s hard to believe that if the Skunk Ape does exist, there is no photograph of it, and yet it’s still compelling to look at these blurry images. The stillness of photography creates the illusion of the real. Is that something that you’re interested in?

FAQ Oh yes. I watch a lot of Ghost Hunters when it’s on TV, and it’s a terrible show, but I’m always interested in the kinds of ludicrous equipment they’re using. I also love the really terrible documentation of the Loch Ness Monster or the Yeti or fairies. When I was a kid, my sister gave me this incredible book of fake [photos] documenting this young girl’s experience with fairies in her garden.

RS The Cottingley Fairies.

FAQ Yeah. I thought it must be real because it’s photographed. So, yeah, I do think about that a lot in my work. I don’t digitally alter, so I’m always interested in how to create the conditions for a magical experience that a photograph can then come out of. I think it’s about engineering a situation rather than an image, and then the image becomes evidence of the situation. So people often ask me: did that really happen? And to me that question doesn’t matter at all, unless I’m on a journalism job. Otherwise, my work is about these moments of fantasy and fear that are manifesting all around us, and for me the photographs are the evidence.

Ross Simonini is an artist, writer and musician living in New York and California