The artist’s elusive silk paintings draw on a dizzying range of literary references, but what is lost in translation?

Creatures skitter and drift across a series of 14 variously sized wall-hung silk paintings titled after Tang dynasty poet Li Shangyin’s lament ‘The Sad Zither’. (Li’s poetry is known for its use of imagery and symbolism to describe the elusive qualities of human emotions.) But you might not notice them immediately, hidden as they are within the murky, brackish colours that flood Hao Liang’s seemingly serene land- and waterscapes. It would be easy to say that Hao is following in the centuries-old Chinese tradition of shan shui painting (literally, depictions of mountains and water); and in those terms, the work is not exactly groundbreaking. However, Hao adds a curious and unsettling quality to what is traditionally a reflective and precise artform with works that also operate via degrees of obscuration, rather than a search for Daoist simplicity. A delicate blue octopus floats mysteriously in the muddy blue waters of Poetics of Li Shangyin III (2021); in Divine Comedy II (2022) a tiny devil standing on a tree branch reaches out with raised arms while a snake rises from the ground to watch a lone passerby make his way through gloomy woods; in Under a Tree in Britain (2022) a flock of birds, the intricacy of their rendering only noticeable on close inspection (a fine showcasing of the detailed brushstrokes required of the gongbi style), flit past a seated meditating figure and in the direction of a waving human-monkey hybrid. Literary references to other stories – by Dante and Jorge Luis Borges, among others (and helpfully expanded upon by the gallery handout, which simply provides various passages and verses that inspired Hao) – crop up in those latter titles, adding yet more potential layers of interpretation to the paintings; Li’s ‘The Sad Zither’, however, is quite enough dot-connecting to be getting on with.

An English translation of the Li’s poem is provided on the gallery’s paper handout. But translations can be tricky: no two are the same, specific word choices are subject to the translator’s interpretation and in the case of Li’s poem, references to classical Chinese stories are left out in favour of allowing a more straightforward understanding of the verses. For example, two translations of the same line might read: ‘With sunburned mirth let blue jade vaporize!’ (the translation used by the gallery); and ‘From sunburned jade in blue fields let smoke rise’ (from Xu Yuanchong’s 2009 translation). To some readers, the latter translation might better reflect Hao’s overall palette; to others, ‘sunburned mirth’ might offer a subtler emotion-led interpretation, and an invitation to look for this among the generally morose and sullen faces of Hao’s painted figures.

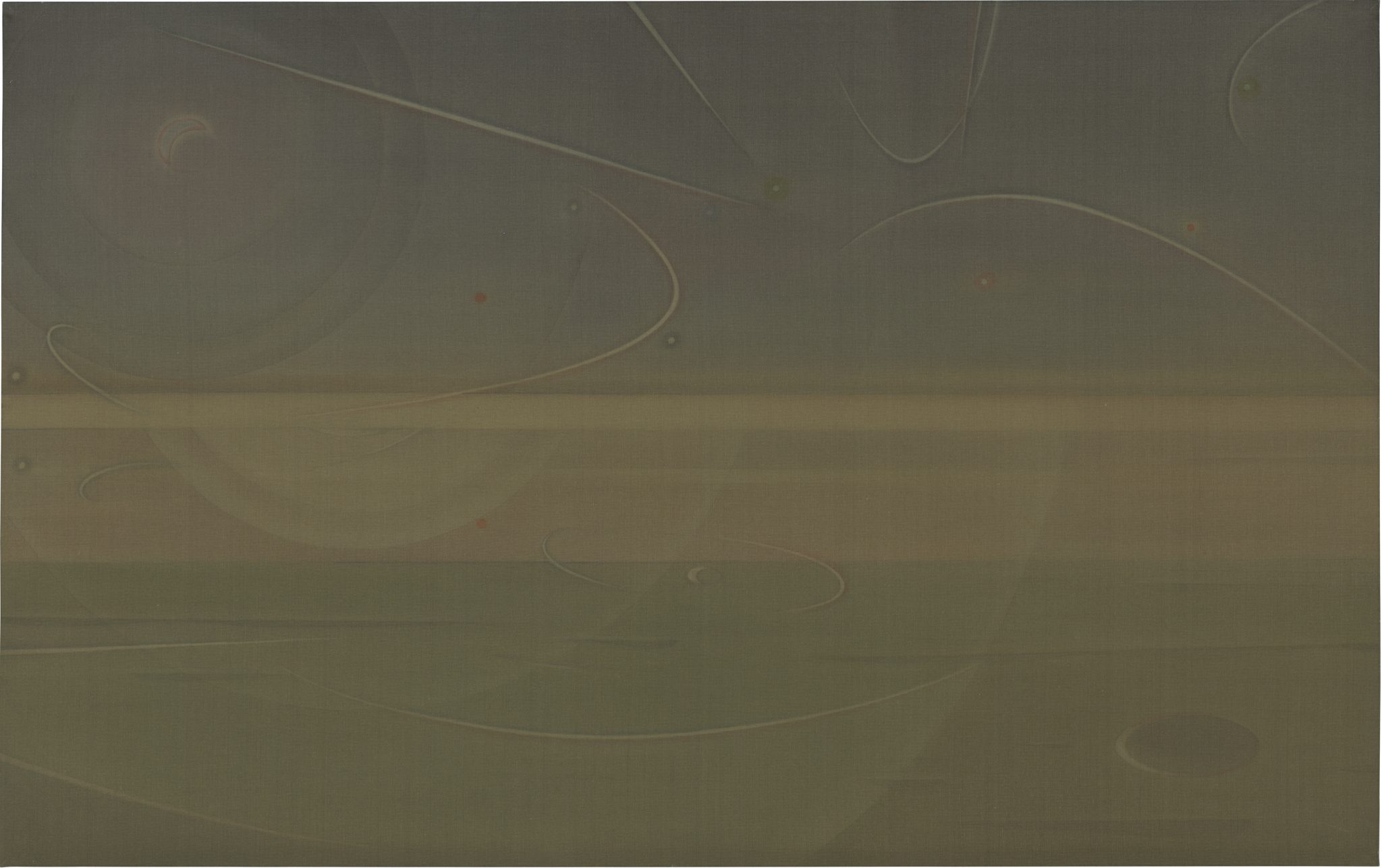

Other moments of obscurity occur in paintings like All Things and Floating Grass (both 2022), which appear to be abstract, but whose titles invite a figurative reading: the drifting, swirling patterns of All Things might refer to something as vast as a landscape, or to something as minute as bacterial growth seen through a microscope. Floating Grass affords a little more in the Rorschachian game of spotting familiar shapes: the eye of a fish here, some pondweed there. But it’s in eeriness that Liang’s paintings achieve a sense of delight. Gatha by Ikkyū (2022) depicts three tiny figures making their way along the edge of a river that runs through a forest. The scene almost looks idyllic – and yet something is off: a close look reveals that one of the figures, with a not-quite-human face, also happens to have the hoofed leg of an equid. Next along the wall, a ghastly dull-green face suddenly looms through foliage in Spring and Emaciated Horse (2022): eyes half-closed with the hint of a gurning grin about his mouth, the stoned peeper (who is, as far as what’s visible, a human rather than a horse), so jarring in mood and tone, pays no attention to the viewer – merely stares off into the distance, sporting a skeletal torso, while we are left to contemplate his many minute and disgustingly visceral red pimples. Amid the waiting and wandering figures that populate The Sad Zither, this painting offers a moment of unexpected sunburned mirth.

The Sad Zither at Gagosian Grosvenor Hill, London, 9 February–18 March 2023