The late artist forged a new vernacular of a muscular, radical femininity

In a way, the passing of Portuguese-British artist Paula Rego last week seemed improbable. Her place in the pantheon of artists had been secured many decades earlier, given the frequency with which she was included in the permanent collections of the world’s leading art institutions. Recent retrospectives at Tate Britain, the Scottish National Gallery and the Irish Museum of Modern Art caught a mass audience in thrall to the dreamscape of her subjects, where impish creatures run amok and stubborn undergarments impede their heroines.

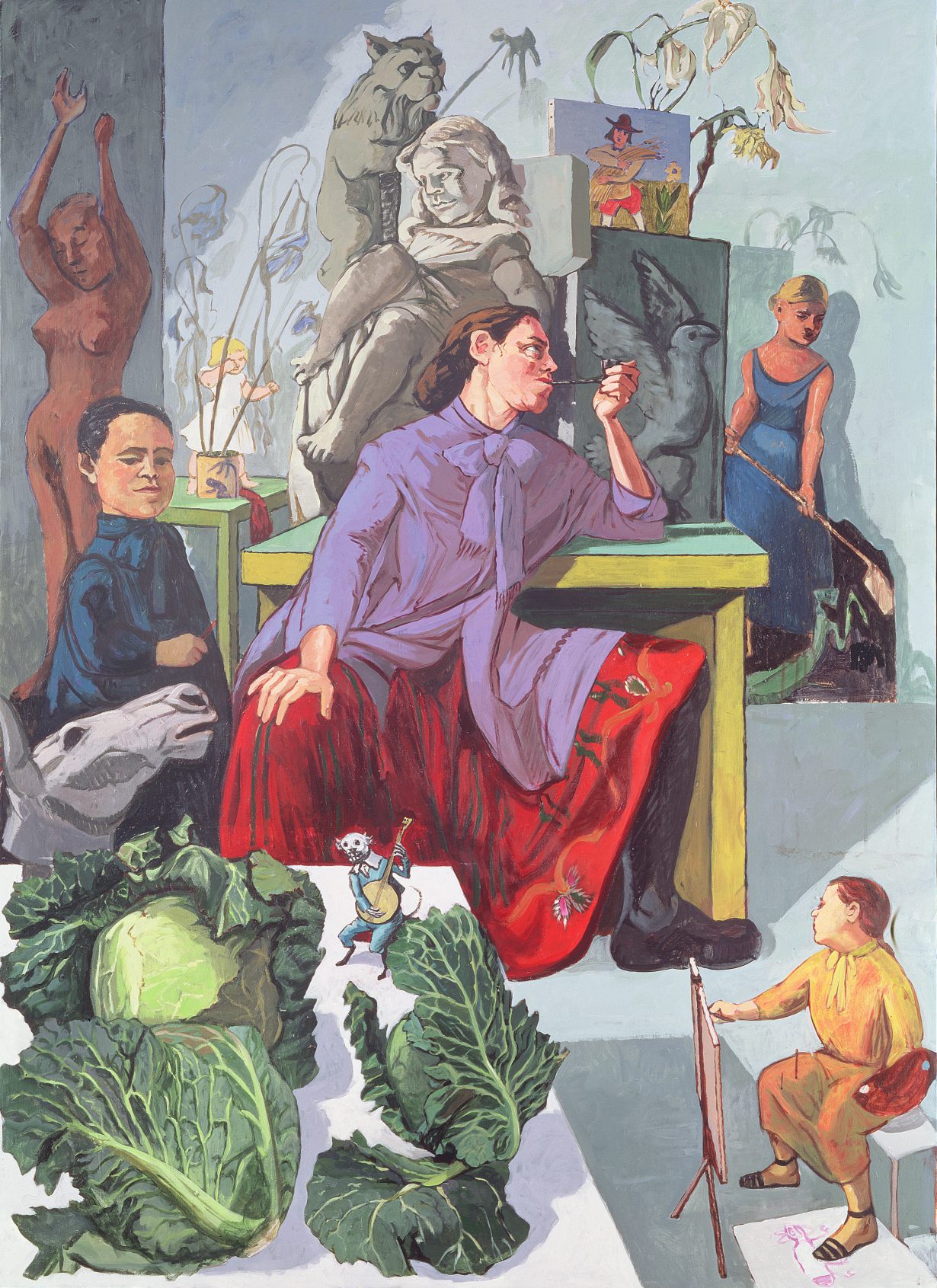

Rego’s contribution was to reject an artworld created by and for men, and not just in her depiction of women, but in the blithe indifference she embodied towards the artworld’s cult of ego and fixation with notoriety and mystique. Her work in its entirety may be read as an assault on that very cult, reframing such mystique as a formal imposition placed on women that necessitates their quiet submission and request for male approval. Instead, in her body of work she forged a vernacular of radical, cartoonish proportions: a chaotic horror vacui, garish, puerile, loud, simultaneously also whispering and slight.

The female figures for which Rego is best known were created in such large numbers as to supplant tepid stereotypes propagated over millennia. Today, and as a result of this effort, a strong, muscular femininity is etched into the world’s galleries, a femininity often found in the completion of some task, be that polishing a boot, plucking the feathers of a goose or unpicking the swirling vortex of subliminal despair. Breaking loose of the formal constraints imposed on her since the beginning of time, the woman is free to writhe, stomp, be hell-bent and astride, occupying and expressing an imaginary composed of forces – of folklore, storytelling and intuition – that had been denigrated and suppressed by a patriarchal empiricism.

It is not as if the expectation of composure eluded Rego’s women, however. What we get in her paintings is a construct of women who are first and foremost taut as a result of being pulled in the two opposing directions of desire and societal expectation. Scenes range from the farcical to the nightmarish, from scabbard-wielding maidservants to moments of tense domesticity painted over with a smile.

Perhaps the most confrontational scene is that of the woman lying prone. If not in the alluring spectacle of her visible face, breasts and torso, perhaps the female figure in painting could serve a role less agreeable, more political, Rego’s images suggest. She produced a series of ten, large-scale paintings based on scenes from backstreet abortion clinics, credited with swaying public opinion in legalising abortion in Portugal in a referendum of 1998. In their frank portrayal of the isolation and claustrophobia of that experience, they recall the short story ‘Tiger Bites’ by Lucia Berlin (2015) – fitting given the literary character of Rego’s work (she famously drew inspiration from Eça de Queiroz and Martin McDonagh among others). The allusions range from the overt to the oblique. Even in abortion, Rego appropriates scenes familiar to art history, albeit then only as an invitation to sex. Rego’s paintings serve to remind us that those same poses are needed in expelling the fruit of that sex, long after the male cocreator has departed.

Cast the mind a little further back and we find that the prone woman is not altogether absent from art history. We have seen her face down and suffering once or twice before: at Calvary and the resurrection. These are scenes of pain being directed to a man, and not uncommonly, his feet. Rego rejected the Catholicism of her upbringing in Lisbon, and the subversion of religious iconography is ever-present.

She understood that the estrangements of physical agony, but also gender, dual nationality, single parenthood and infidelity, are libidinal. That the plight of the subjugated, beyond the material struggle, is to live with a well of unresolved longing, dissonance and confusion. For those of us who could never really square with Leonora Carrington, finding something perhaps too fay and too wispy in its phantasmagoria, Rego provided solace: a surrealism for the broad-shouldered and sturdy-legged, the working people whose imaginary life is no less vivid than the wealthy and the powerful, at whose hands it had been erased.

It is not the art of social realism, but that does not mean that Rego did not deal in the subject of class. She transformed conventional ideas about the artist – an entity belonging to a class of its own, supposedly. This was done as much in her person as in the work, the grand stature of her legacy belied in the small, affable figure who still made public appearances as recently as 2019, collecting awards, smiling for cameras, enjoying her success in bright colours, bold eye-makeup, and an exquisite array of jewellery. Far from being facile, this is just the kind of observation permitted in a post-Rego world, one that has been freed of the prejudice that women need always to be serious, or abject, or self-annihilating, for their genius to be seen.