A contemporary project considers the use of sacred historical imagery, renegotiating our archival and colonial impulses

This is a story with many beginnings, and many possible endings. One starting point might be the Hopi people and their culture, who have for thousands of years been part of the arid southwest of what became known as the North American continent: a culture of oral histories and traditions based around stewardship of the land. Another starting point might be the European and Anglo settlers and homesteaders moving West across the continent during the nineteenth century to claim land, and the accompanying treaties and betrayals that saw Native Americans pushed into reservation silos and forced into assimilating with these newcomers, and their sense of property and propriety. Or it might begin more specifically in December 1895, when a young German man was brought to Hopiland by a Mennonite missionary. The German brought with him a handheld camera, taking a few dozen hurried and out-of-focus shots of what he saw in the villages, including several of the Hopi’s dances and seasonal rituals. By the 1930s, in response to the commercial exploitation and wide publication of sacred imagery, the Hopi had banned visitors from taking photographs entirely; and though the German man never publicised his photos from that trip – and asked that they never be published – after his death, in 1926, they were printed in books, in 1939, 1988 and 1995; and even after requests from the Hopi to cease their publication, they were published again in 1998, and yet again in 2018.

My own knowledge of this story begins in 2018, while visiting Camera Austria’s exhibition space in Graz, where German artist Ines Schaber was showing a sparse selection from her Notes on Archives series, a sprawling project that, since 2004, has examined the realities and contradictions of photographic archives. Schaber’s exhibition was restrained, but full of tensions and hidden histories; mapping, for example, in Culture Is Our Business (2004), how an image of street fighting during the 1919 German revolution came to be part of both a commercial stock-photo agency’s catalogue and a historical archive. The historical archive narrated the photo as depicting a cross-class group of revolutionaries defending a paper factory; the commercial agency describing the same photo as the inverse, of the Imperialist army defending against insurgents. Her Picture Mining (2006) asks us to reflect on what images can achieve when it traces photographs of American child miners from the 1910s – intended at the time as social commentary – to the same online stock-photo agency, returning the underage workers to another version of commercial exploitation.

For me, one of the side effects of recent months of protest and lockdown has been an involuntary retrospection, looking to things experienced several years ago as they find resonance with our uneasy present. Among the images of violence that pop up unbidden yet again on social media timelines, among the blinkered decrying of pulling down certain statues as the ‘destruction of history’ and among art institutions treating these issues like live mines that should be avoided rather than publicly dismantled, one of the things I found myself thinking of was the layered, hard-eyed archaeologies in Schaber’s project and the implicit questions it poses: how do these images actually come to appear on our screens and in our lives? And what histories are they really telling? What are we seeing, and when do we look away?

Culture Is Our Business (2004). Courtesy the artist and Camera Austria, Graz

One corner of Schaber’s exhibition featured Unnamed Series (2008– 09), a set of actions responding indirectly to the publishing of the 1895 images of the Hopi, produced in collaboration with fellow artist Stefan Pente. On one wall was a set of fairly nondescript photographs of doors and backlots in Santa Fe, taken by the American photographer Karen Peters. Next to that was a slide projector with no slides in it, facing towards a whited-out rectangle on the wall. It wasn’t running, but putting on a pair of headphones that accompanied the work, Unnamed Series, Part 2 (2009), you could hear dictated a letter that Pente and Schaber had written to the person who had taken those images back in 1895: art-historian Aby Warburg.

“Dear Aby,” they read, “If we are to show you these images and accompany them with our words and thoughts, we do so to share with you our concerns about the taking of pictures and their growing life. We know that we will not be able to make them disappear, but we hope that we can help them become something else. What were they supposed to represent? What are they representing today?” Warburg’s visit to the Native Americans of the southwest has gained a mythical status among the art historian’s fans and scholars. He had spoken only intermittently of his trip in the years after, but most notably, after suffering from depression and spending several years in a mental asylum, gave a lecture with accompanying slides about his understanding of their symbology to a small audience at the asylum, in order to prove his mental health. In the lecture he compared the rituals of the American southwest’s ‘enclave of primitive humanity’, as he called it, to similar imagery in Ancient Greece and medieval Christianity. The trip, and the resulting cross-cultural approach it inspired, is seen as a key to his conception of the Mnemosyne Atlas, his unfinished idiosyncratic crosscultural collage of art and imagery that has been reconstructed and is currently on show at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt in Berlin. Warburg’s photos of the Hopi rituals are conspicuously absent from the Atlas itself; it was a colleague’s posthumous publication of the asylum lecture that released them into the public realm. The images have since spread, as part of art installations by Goshka Macuga and Emo Verkerk, for example, and reprinted in Warburg studies by art historians Philippe-Alain Michaud and Uwe Fleckner. They have spread even further digitally: a quick image search online brings several of them up immediately, while PDFs of the lecture and studies are easily found.

The issue isn’t so much that Warburg himself didn’t want the images published, but how the ongoing use of the images displays a complete disregard for what and who the images depict, and how the act of looking itself perpetuates these problems. These aren’t visibly traumatic or outwardly violent images; they are, as I understand from descriptions, mostly mundane shots from the pueblos, with a few ceremonies in action. The images could even be seen as celebratory, with historical value. As photographs of private rituals, though, the images are seen by the Hopi as a misconstrual of tribe-specific esoteric knowledge. Art historians Claire Farago and Donald Preziosi devote a chapter to this issue in their book Art Is Not What You Think It Is (2011), noting how for the Hopi the issue is not so much one of ownership but of time, understanding ‘sacred presentness as trans-temporal. Privacy is consequently violated every time someone looks at the photographs.’

Pente and Schaber’s first response to Warburg’s photographs was a performative gesture, making a video in which they projected a slide sequence of the photographs onto a wall and attempted to block out parts of the images with their bodies; then they decided that this video shouldn’t be shown – the audio of Unnamed Series, Part 2, with the letter read aloud, is all we can experience. It’s a deliberate distancing that feels appropriate – similarly, in writing this piece, I have attempted to keep my distance from the images of the Hopi, to try not to see them, an individual act of blurring my vision, screwing up my eyes as I scroll. But this seems a private stance that has limited bearing on the wider structural issues. During his visit with the Hopi, Warburg might, as Pente and Schaber imagine in their letter, have “realised that the real limit of the rationalist, modern Western mentality is its tendency to negate things that cannot be measured”, but any doubts Warburg might have expressed about such rationalist approaches haven’t stopped the voracious completists who study his work. Reverence for a European art historian and a short tourist trip he took over 130 years ago takes precedence over a differing cultural approach; and so the archivist impulse repeats the colonial impulse.

Unnamed Series seems to exist in its primary form as a publication, in Notes on Archives 5 (2019), the book collecting together views such as Farago and Preziosi’s, as well as the exchanges between Leigh Kuwanwisiwma of the Hopi’s Cultural Preservation Office (HCPO) with the Warburg Institute. ‘Only members initiated into these societies hold its information and knowledge, which is not written, but rather is passed on orally to society members who participate in the ceremonies. Information about the significance and function of these ceremonies can only be given by those initiated into these societies,’ Kuwanwisiwma wrote. Kuwanwisiwma’s predecessor, Vernon Masayesva, helped set up the HCPO and, in 1994, had contacted a range of museums and archives with holdings of Hopi cultural artefacts and documents, requesting a moratorium on the presentation of anything that concerned religious or ceremonial practices, and asking that the materials be returned. Several institutions shifted their stance and limited access to such photos and drawings after that; but in 1998 the Warburg Institute defended its republication of the images by stating that they were already in the public domain. It was, of course, the Warburg Institute that published the original lecture and images in its journal in 1939, against Warburg’s wishes, putting them into the public domain in the first place. The gesture (or lack of one) continued an ongoing vicious circle, in which photos already circulating only continue to circulate, a process only sped along by digital archives and quick image searches.

In Notes on Archives 5, Pente and Schaber acknowledge the limitations of their cautious and academic project, noting how when it was exhibited in Europe it was interpreted as institutional critique of the Warburg Institute. When shown in the US, however, it was criticised for sidelining the Hopi and maintaining Warburg at the centre of the narrative, repeating the hierarchies created in publishing the images. ‘It is not enough’, they conclude, ‘to not speak on behalf of others.’ The issue might not be theirs to resolve, but they suggest several ways to continue the conversation, one being a conceptual reframing. Theorist Ariella Azoulay, who was driven by the brutal imagery emerging from the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, proposed viewing any photograph as an implicit civil contract between the person taking the image, those photographed, and those later handling and looking at the image. It’s a powerful suggestion, which if taken seriously would heavily impact the imagery that assails us daily, as well as redressing the balance of whether and in what ways victims might choose to be seen. It would seem, though, that any such responsibilities of such a relationship for Warburg’s Hopi images has long been shrugged off by those who align themselves with the art historian. Another suggestion is return: repatriating the images to the Hopi, for them to decide how they might be used. Though this, again, while not entirely impossible for physical holdings, seems an idealistic suggestion in light of the digital dispersal of the images. It is not enough to accept they are just in the public domain, as if innocuously placed there; whose public, what domain? What are the so-called rights of such an eternally present photography, where traumatic transgressions might not be continually reenacted? Like any pictures that appear on our timelines at the moment, legally, of course, we can look at these images; and by ingrained Insta-habit, we want to see them. The question becomes whether we decide to look.

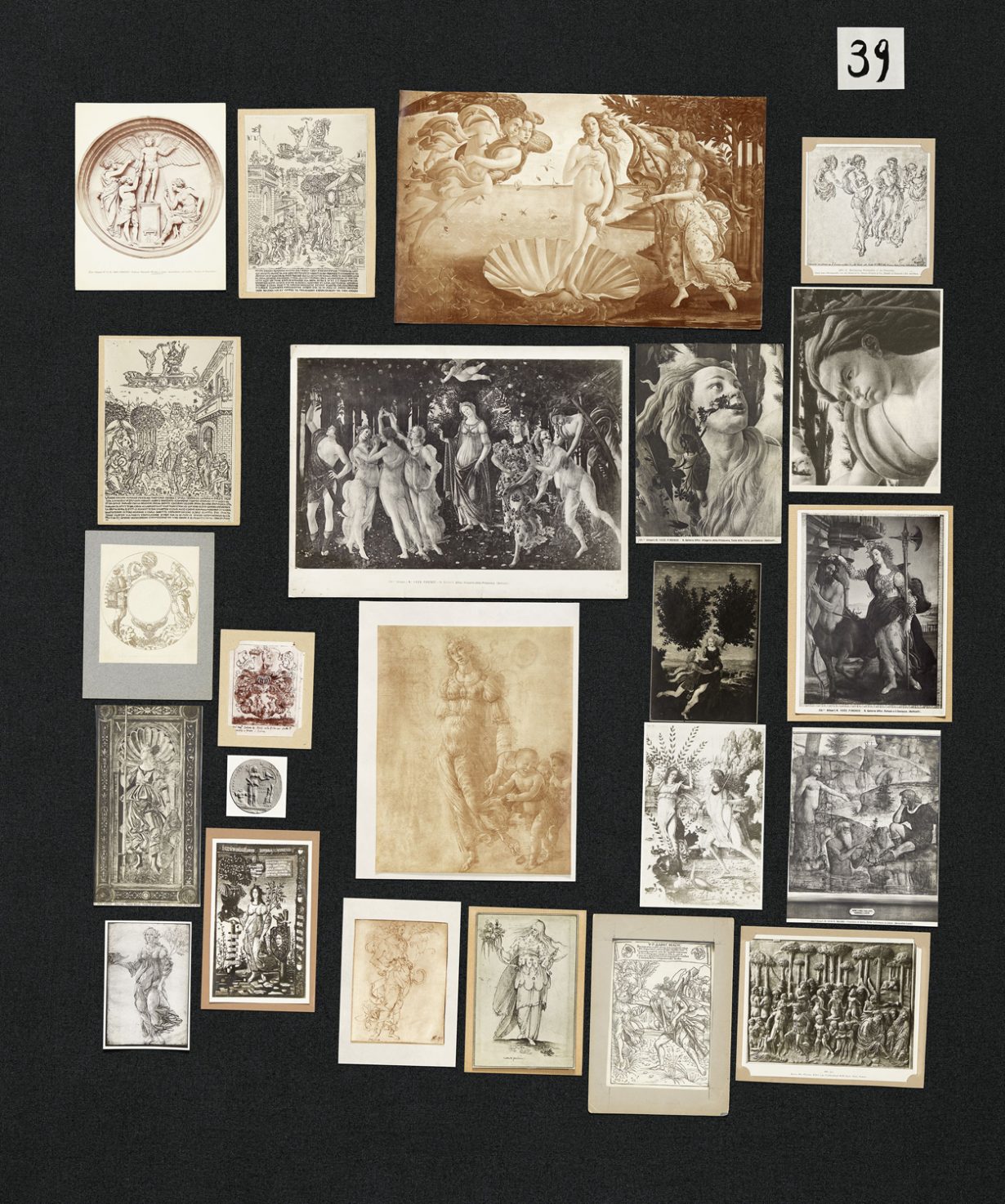

As Warburg’s work is in the public light again in the coming months with the exhibition of the remade version of the Mnemosyne Atlas, a strategic reinhabitation might prove useful. The uncompleted Atlas provides an arrangement of unlabelled, uncaptioned images over a set of themed black-felted panels. In a notebook, Warburg described the project as an ‘iconography of the intervals’, a place to link and compare recurring symbols from a range of eras and sources. But the interval is also literally the gaps between the images pinned to the felt. In light of the Hopi’s pointed absence from the Atlas, these spaces and intervals become apparent as something active, something political – a place to step back, a space that might be filled with other perspectives than your own, something deliberately withheld, that is not yours to see.

What Unnamed Series seems to be, rather than just a conceptual gathering of images, text, and an occluded video, is more a model for informed non-Hopi audienceship – whether European academics, Americans rehashing frontier nostalgia, or just casual browsers – proscribing a deliberate aversion that might then be spread beyond just a personal act. A first, practical step is a choice not to look at such images, and the project asks others to consider that choice. Not as an act of self-censorship, but as an act of respect, of patience, an attempt at redeeming a civil agreement created through an image; you look when that relationship is actually agreed, actually civil – whenever in time that might be.

Chris Fite-Wassilak is a London-based critic and author of The Artist in Time (2020)