Why the Greenlandic artist thinks photography is uniquely suited to telling the story of his homeland

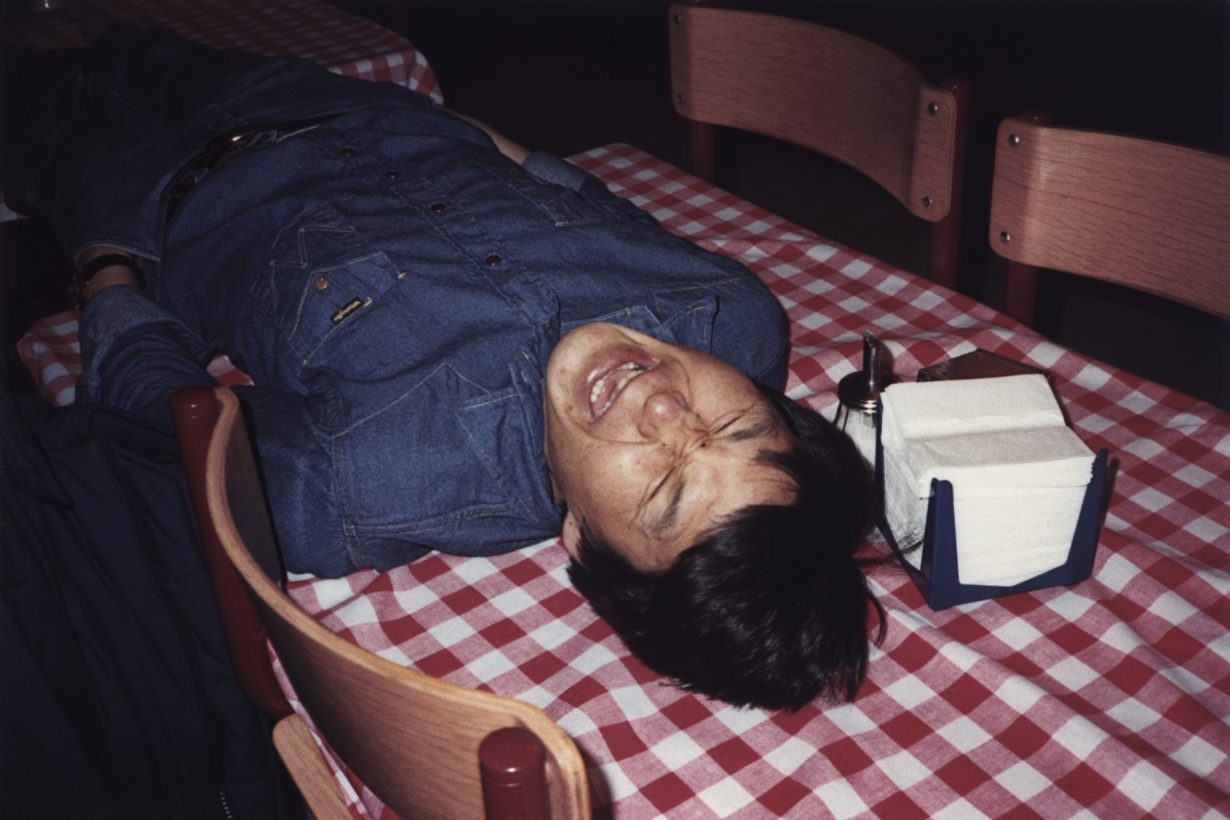

A few years after graduating from the International Center of Photography on New York’s Lower East Side in 2016, Inuuteq Storch published a series of images that had been made using a pink plastic analogue-camera once owned by his sister. Flesh (2019) speaks to the photographer’s yearning for his homeland of Kalaallit Nunaat (Greenland in English). He’d previously studied at the Fatamorgana photography school in Copenhagen; in New York Storch felt newly rootless. Flesh captures this particular moment, when Storch was searching for the familiar in unfamiliar surroundings, through snapshots of subway benches, Christmas decorations, stray cats and jocular friends. While homesick, Storch was also enjoying the distance that brought his cultural identity into focus, alongside a desire to photograph Kalaallit Nunaat. “It was a dream come true to move to a city like that as a young man,” says Storch – who’s now in his mid- thirties and lives back in Kalaallit Nunaat – over email. “Another realisation you get [is] the importance of home. I love New York, but I love it more for letting me realise that we belong at home.”

The place that home has in Storch’s heart is at the forefront of his first exhibition in New York, at MoMA PS1 this autumn. Soon Will Summer Be Over will survey the past ten years of Storch’s output, filled with nostalgia and warmth for the lives of the Kalaallit, which register here as disarmingly ordinary. “I don’t know if my work has evolved, what if it has devolved?” wonders Storch. (His materials, at least, have changed somewhat: these days Storch uses three different cameras – an old Zeiss Ikon for black-and-white 120 film, and two others for 35mm colour and 120 positive film.) Beyond being documentary in nature, these images are deeply personal – we have the feeling that Storch knows the people and places depicted intimately. And wants the viewer to feel just as at home as he does. “I’m from a small community in a quite different part of this planet,” he explains. “I hope people can see how diverse this planet is.”

The exhibition title mirrors that of a 2023 series taken in Qaanaaq, one of the most northerly settlements of Kalaallit Nunaat and one of the last to be colonised by Denmark. It’s a place where the sun shines nearly 24 hours per day in the summer. Framed by the otherworldly Greenlandic scenery, the mundane moments of kids riding their bikes or neighbours sharing a cigarette deny any instinct to ‘other’ Kalaallit Nunaat; instead it comes across as a vibrant living, breathing place, imbued with beauty and banality. This is also a curious moment of reflection for the photographer, whose reputation has soared in recent years thanks to his representation of Denmark at the Venice Biennale in 2024. There, Storch’s presentation Rise of the Sunken Sun made him not only the first photographer and youngest artist to represent the Kingdom of Denmark, but the first Greenlandic artist too. The display of several hundred photographs brought to light stories of both individuals and communities, and their connection to the wild landscape.

Storch’s burgeoning reputation reflects a growing interest in Greenlandic artists among the Danish cultural establishment, alongside such names as Pia Arke and Jessie Kleemann, spurred by the wider artworld’s recognition of Indigenous and minority voices as well as a global push towards decolonisation. Storch, though, seems unaware of his newfound position. Certainly, when he was asked to take on the Danish Pavilion, he did not grasp the importance of the Venice Biennale. At the time, he admitted that he did not attend that many exhibitions or consider himself much of an art expert. Similarly, when it comes to his first solo show in New York, Storch is still not sure what it means to him. He notes, “Life is kind of funny in a way that you actually understand things later on.”

He has been purposeful, nevertheless, in establishing the foundations of a Greenlandic photographic culture, through his own work and by collating the work of others, both known and anonymous, historic and contemporary. Rise of the Sunken Sun notably included archival images by the first professional Greenlandic photographer, John Møller; the latter documented foreigners who found themselves in Kalaallit Nunaat between the 1880s and 1930s. Storch stumbled on Møller’s photographs quite by accident in the Greenland National Museum and Archives. (He’s previously explained that he began to make use of archives after a fortuitous night spent dumpster-diving in his hometown of Sisimiut, where he discovered rolls of films.) In a 2025 exhibition in the foyer of Politiken’s headquarters in Copenhagen, Storch created an installation of archival photographs from the Danish newspaper that depicted Kalaallit Nunaat, inviting visitors to ruminate on how the country has been represented by outsiders through history. Spanning 100 years of photojournalism, these blown-up images from newspaper clippings offered a vision of the Kalaallit from the wide-eyed view of the press.

Storch’s perspective is, of course, altogether different. The series Keepers of the Ocean (2019) pictures Sisimiut, in the central west of the country, home to some 5,500 people and the artist’s father’s patisserie. The untamed vistas of sea and ice mingle with details of friends, family and daily existence: a young woman tugs the lead of a Qimmeq sledging dog; a cigarette-toting teenager leans out of a yellow Cadillac; washing is pegged out to dry overlooking a dramatic coastline and abutted by a motorcycle. Here, Storch’s honest portrayals dispel mythologies surrounding the world’s largest island and permit a deeper understanding of individuals on their own terms. We are almost given permission to forget what we think we know about Greenland – such as its supposed primitivism and isolation from the outside world.

Kalaallit Nunaat was a Danish colony between 1814 and 1953, before it was recognised as its own self-governing territory within the Kingdom of Denmark. The Danes have been forced to reckon with the legacy of their colonialism in recent years, following mounting political pressure. There are dark moments they would sooner forget, such as the placing of Greenlandic children with Danish families through the 1950s and the forced sterilisation of women in an effort to reduce the population during the 1960s and 70s – an act the Danish prime minister Mette Frederiksen apologised for last August. The Greenlandic school system now employs the Danish model, and shamans have been replaced with Christian priests. Storch’s first photobook, Porcelain Souls (2018), collated photographs taken, and letters written, by his parents when they were young, between the late 1960s and early 80s. The series captures a fairly ordinary coming-of-age story, but one set against an extraordinary backdrop. Handling these images, Storch recalls, he felt that everything might soon fall apart and the traditional way of Greenlandic life disappear.

Storch has suggested in the past that photography is a medium invented by the West, an idea which Greenlanders have adopted. This form of storytelling is, nevertheless, a natural fit with the Greenlandic sensibility and creative instinct, as it is through stories rather than written histories that the Kalaallit have documented knowledge. Storch also appreciates the wordless nature of photography, making it readable to everyone without explanation.

For Storch, the Danes opened a door to European thinking, while the Greenlandic people gave the Danes access to the spirits. “I have noticed that Inuit are very spiritual, and I believe we used to live with spiritual beings not so long ago, and therefore we are still quite connected,” Storch explains. The haunting photobook Necromancer (2024), made in light of the COVID-19 pandemic in Greenland, reflects on this innate connection between the celestial and profane. In Greenlandic belief, souls can linger and still be reached even after death. In contrast to other series, these grainy images of Kalaallit Nunaat are imbued with an eerie atmosphere – intimate and mournful – as cars journey through snowfalls, boats are abandoned and the shadow of a solitary figure is projected onto the landscape.

Storch’s photographs reveal how long-held traditions have become intertwined with European modernity. In At Home We Belong (2010–15), Storch reflects on the openness of Kalaallit Nunaat to the outside world, importing the majority of their day-to-day materials and exporting fairly little in exchange. In these intense black-and-white images, the details of clothes, industrial equipment, pipelines and even bicycles refer primarily to imported goods. There’s a surrealness to, say, a fisherman pulling in his catch while wearing an American-style baseball cap, or a blindfolded, gun-toting woman on the side of a road, dressed as a dominatrix.

Greenland’s trove of natural resources and strategic Arctic position have, of course, become the subject of international debate in recent years. The Trump administration has not ruled out plans to annex Greenland after the Danish government rebuffed offers to buy the island. It’s hard to separate an exhibition of Storch’s photography in New York from these mounting tensions. For Storch’s part, he does not see his work as explicitly political – his images are far more personal. “Photos are maps of my mind and emotions,” Storch explains, a format or process he dubs “Identityography”. “I find it strange”, he adds, “how ‘feelingful’ [photography] is, even though it’s such a mechanical form for expressing yourself.” And yet, Storch can understand why his images might become political. For they inevitably reflect the shifting effects of outside influence, not least by potential colonisers and climate change.

Storch evidently feels uncomfortable talking on the subject. Instead, he speaks in more spiritual terms: “I have a feeling about this universe that its nature is to change – and, because of that, everything is made to change with time,” he says. “Even time changes, depending on where you are. I also wonder how my work might change with time. Let’s see.”

Inuuteq Storch: Soon Will Summer Be Over is on view at MoMA PS1, New York, 9 October – 23 February

From the October 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.

Read next: How Pia Arke reconstructed ‘Greenlandness’