In drawing out a seemingly bizarre historical immigrant experience, Lebanese artist Joyce Joumaa reminds us how little has changed today

Before Memory Contours (2024) can be seen, it can be heard. The sound of waves: a million droplets hissing as they move independently but in disordered unison. Amid that, the calls of seagulls; voices listing names and giving instructions to direct other people; the movement of chairs echoing off the hard floors of spacious halls; the rub and scratch of pencil on paper, amplified to merge with the rushing waves. This soundscape plays through speakers in the four corners of the final room in the International Pavilion, one site of Adriano Pedrosa’s exhibition Foreigners Everywhere, at the current Venice Biennale.

The work is by Lebanese artist Joyce Joumaa. Raised in Tripoli and now based in Montreal, she has to date been concerned predominantly, via video and installation works, with epistemological and postcolonial understandings of Lebanon, particularly in relation to space and architecture as sites of power. More recently she has begun to explore other geographies, and Memory Contours is a testimony to US immigration procedures during the early twentieth century and the qualifications for entry to the ‘land of the free’. We might like to think that, in the century since, much of our social and political regard for migration has changed, but the reality would suggest otherwise. Recently in Italy, as Joumaa opened her show at the landmark cultural event, Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni was meeting with the Tunisian president Kais Saied, offering business and investment to bolster Tunisia’s control of illegal migration. In November, Meloni also signed a deal with Albania for the Balkan country to detain people intercepted by Italy in the Mediterranean Sea. And in March, human-rights groups resumed calls to close Italy’s migrant centres, labelled ‘blackholes for human-rights violations’, following the death of a man being held at a centre in Rome and a series of other suicide attempts there.

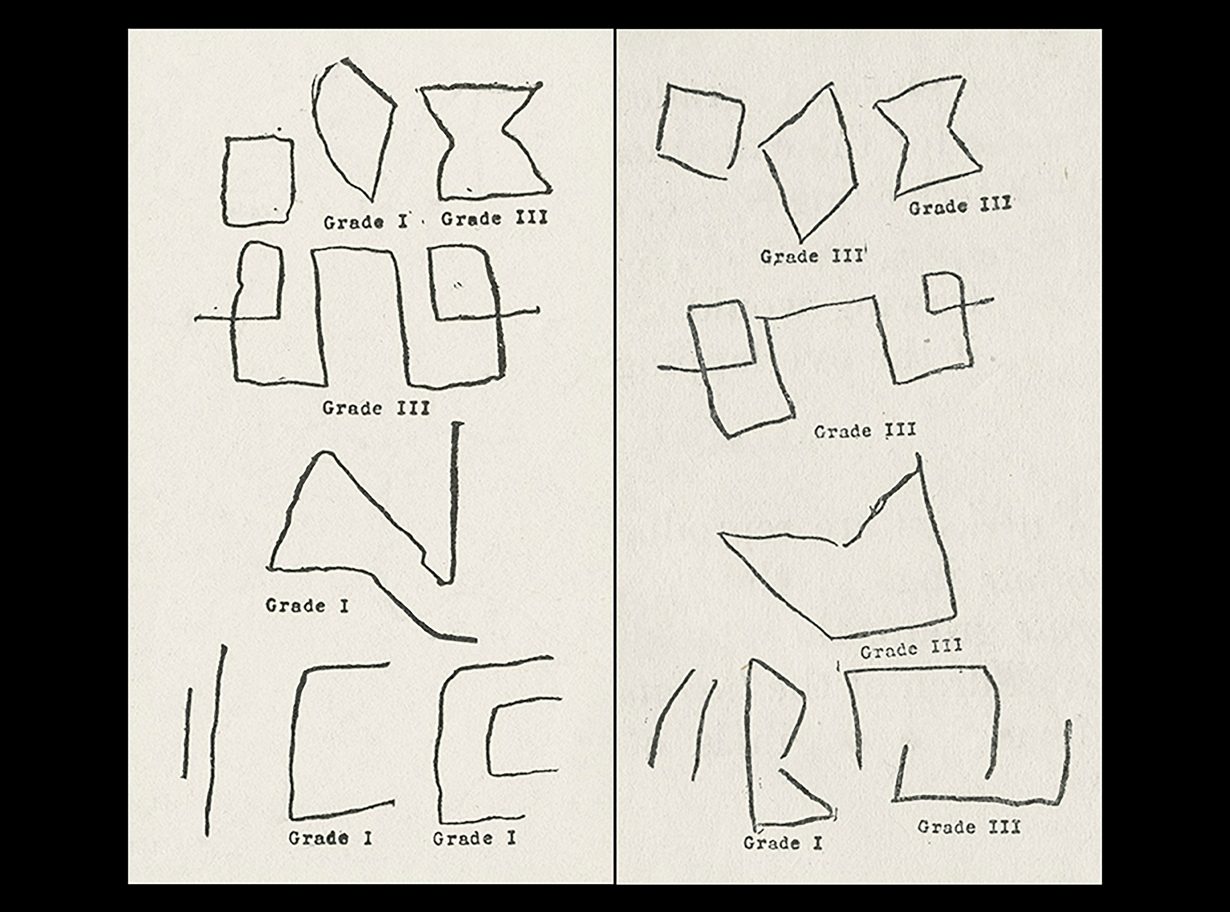

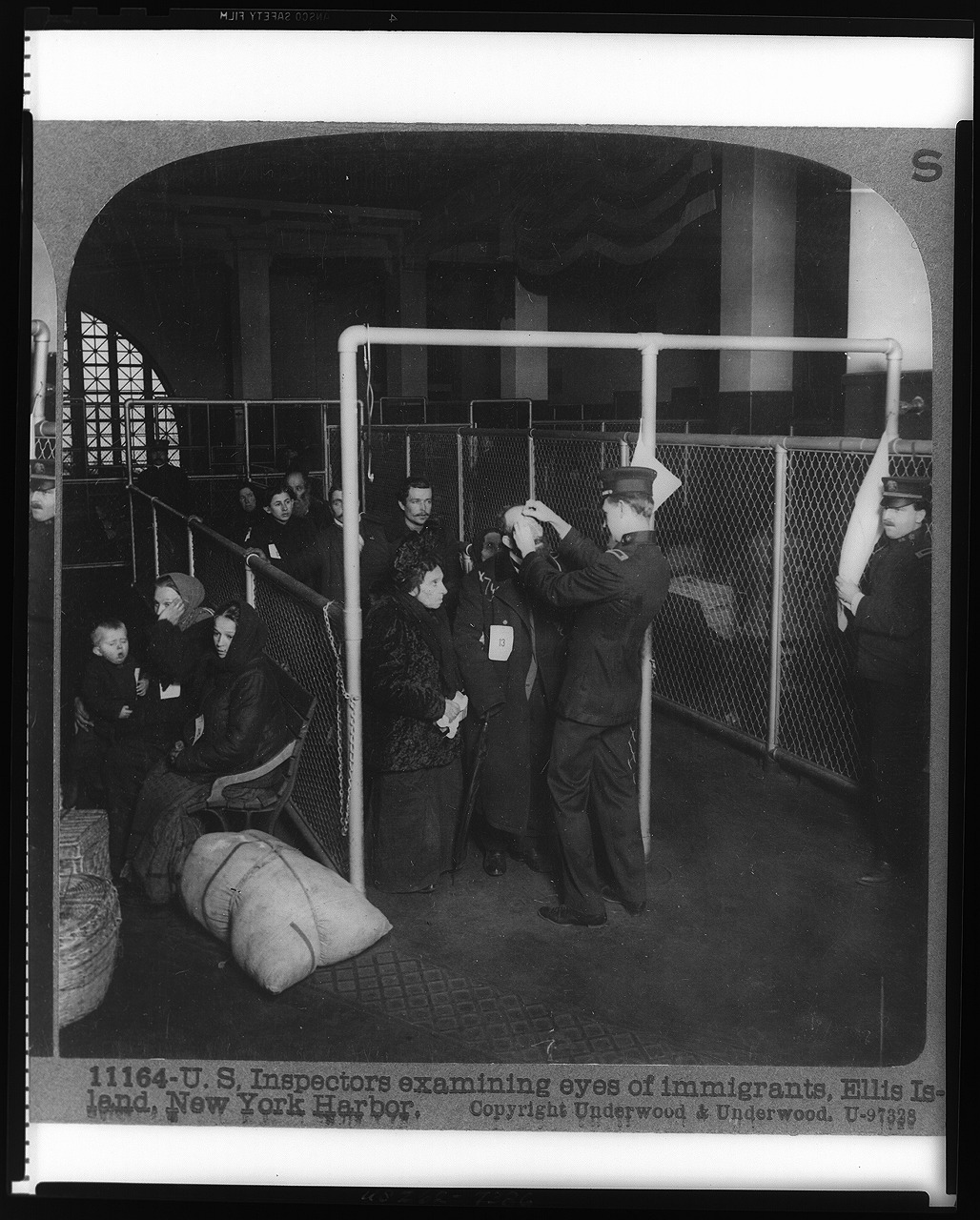

None of these connections are readily apparent on one’s initial encounter with Joumaa’s work. Four metal pillars are arranged irregularly around the middle of the space. Each supports a pair of flatscreens, installed vertically and back-to-back, with the pillar sandwiched between. In each pairing, one screen plays a video recording of a hand drawing on a piece of paper. It’s shot from the perspective of the eye of the drawer, so that we see, out of focus, the pencil’s eraser-end dancing around in the foreground, while the hand that grips it appears in sharp focus, with knuckles crimping and extending like piano hammers. It’s difficult to see what’s actually being drawn. The other screen offers a series of still images of roughly drawn geometric shapes, each numbered as if for classification or record keeping. The exhibition text tells us that these are in fact archival reproductions of responses to the ‘intelligence’ tests assigned to immigrants arriving at the Ellis Island processing station in New York; and that Joumaa lifted them from the 1914 US Public Health Service report ‘Mentality of the Arriving Immigrant’. The tests required participants (a euphemism) to draw shapes from memory, the quality of which would be used to determine their ‘mentality’ and mental proficiency, or identify their supposed lack thereof. Consequences of ‘failing’ the tests ranged from barred entrance to forced sterilisation. It’s estimated that over 12 million people were processed on the ‘Island of Tears’, as Ellis was often dubbed, throughout the roughly 60-year period of its functioning, almost three-quarters of them arriving between 1892 and 1914. For the US government, Ellis was a trial space for the aforementioned tests, to set the basis for wider adoption at immigration centres around the country.

Joumaa’s primary success is the communication of a sensation before knowledge: to garner the experiential texture of another’s experience as well as a logical understanding of it. “I, for the most part, consider myself a research-based artist,” Joumaa told me over a video call a fortnight after the Biennale’s opening. And for Joumaa, research-based artists can too often get away with “providing historical or archival elements that only hint to the concepts that we’re trying to talk about”. In isolation, Joumaa’s installation can seem benign. Her videos aren’t interested in the specifics of the drawer – who they are or what they look like, for the people they imitate could have been from anywhere – but their perspective is inherently empathetic: it’s the drawer’s point of view. There’s a delicacy to the visual composition of each video: in soft-focus, a brilliant light falls across the shot, capturing a beauty almost absurdly ambivalent to the more oppressive nature of the immigration centre she’s referencing. Joumaa performed one of the drawings herself, and then cast three others to reproduce by imitation the archival drawings for the camera. Each video corresponds to one drawer, choreographed in syncopation so viewers move around the room to find the videos at varying stages. Look closer still, and things grow stranger: the videos are in fact playing in reverse. Given that the drawing itself is mostly obscured by the hands, which move slowly and almost uncannily, it’s as if they are working away on nothing at all. In Joumaa’s show, the test drawings are Janus-faced: they represent the experience of the oppressed and the historical recording – cataloguing, if you like – of their oppression; they are significant and arbitrary in equal measure. In this sense, the archive is not just a wunderkammer of tangible history but simultaneously an incubator for enacted power.

In the square exhibition space, the wallpaper recalls the rot-yellow paint of the Ellis Island dormitories, which in turn match the yellowed pages of the archival drawings in the videos as if colour is bleeding into our peripheral vision. The archival reproductions, presented as still images, are plain and flat. This source material, after all, has been kept as a record of people’s attempted crossing, hope for acceptance and the derogation of their worth to the tune of a series of rules. For decades, Ellis Island’s immigration centres had the support of the Eugenics Record Office, who directed policy to promote and maintain a ‘superior race’ in the US. Arrivals would be immediately detained in the facility for testing. There was a particular fixation with eyes, as recalled in Ellis Island (1994), a book by the French writer Georges Perec and film director Robert Bober, which makes a multilayered account of experiences on the island through interviews with surviving subjects, archival photographs and a poem by Perec, ‘The Way to Ellis Island’. Any arrivals with the slightest red in their eye would be hurried off to a medical unit as a trachoma risk. Such physical and also mental ailments – ‘L’ for ‘lameness’ or simply ‘X’ for ‘feeblemindedness’ – were marked in chalk on potential immigrants’ clothes, which multiple interviewees in Ellis Island compare to the treatment of cattle. Some passed through fairly swiftly; others remained in this silo for days or weeks, at which point the line between immigrant and inmate blurs.

‘How can things be described? / or talked about? / or looked at?’ asked Perec in ‘The Way to Ellis Island’, beyond ‘dry official statistics’ and the ‘artificial calm’ of photographs. A common tension in research-based art, too, is that of documentation: what one chooses to present; how to construct a narrative away from its original source representation; what the artist may affect that a historian cannot already. Does Joumaa’s artifice, reversing the videos or “undoing the drawing”, as she describes it, signal some wishful desire to undo the past, to follow the pencil with the eraser? “I didn’t just want to replicate the story. Otherwise, I felt I would be engaging in the same violence that was perpetuated against these migrants,” she says. Though nothing is being undone here: her drawing videos are fictional interpretations, or imitations, of what real people were forced to do – and so are at once redrawing and undrawing. As we listen to the gulls in the air, the spray of water in rebound, the graphite scratches and orders being called out, Joumaa locks us in a fixed loop, collapsing the past into the present.

“When you look at the photos of Ellis Island, you see the mass of people, and in contemporary or historical discourse, we always treat migrants as this collective,” Joumaa explains. “It almost becomes intangible.” Indeed, her own father had fled the Lebanese Civil War to Canada during the late 1970s, and didn’t return until the conflict ended in 1990. Joumaa’s Canadian citizenship is in part a legacy of her father’s time there, just one of the estimated one million to flee at the time. “So the idea of focusing on the one hand, and the gestural aspect of this exercise, was about how to dissect that plural rendering.” The Moroccan-French artist Bouchra Khalili, who Joumaa cites as an influence, addresses similar concerns about homogenisation. Khalili, too, focuses on hands and the contact of pen to paper as a kind of expressive extension for an individual. In her video series The Mapping Journey Project (2008–11), a series of people narrate their journeys from the Middle East and North Africa into Europe – tracing their routes on the paper as they go. Like Joumaa’s temporally elliptic installation, The Mapping Journey Project creates a tension between perspective, also placing the camera from a first-person vantage, and synecdoche, focalising hands as actors of our interiority. But Khalili begins at the end, or at least the present – her subjects speak after the fact, and can formulate events into something like a narrative; Joumaa’s are representational, silent, suspended in a moment of transition whose passage is beyond their control. “It’s about the process of becoming a migrant, as opposed to the point at which you have become a migrant. It is always a process.”

Given the wider cultural obsession with titles, identity and status based on a vast nomenclature for subjective experience, there’s something satisfying in Joumaa’s specific focus on Ellis Island. This was an early locus for many contemporary conceptions of transnational identities – cavernous or decrepit buildings of grim potential, for rejection and return on a precarious journey, or acceptance into a hostile environment. It’s an old and proven trick: reaching into the past to find the first ripples of the present. Indeed, who else in the West more generally wouldn’t recognise this control being enforced by their own state too? Ellis Island was for four out of five emigrants a brief stop-by, as Perec writes, ‘the time needed to change an emigrant to an immigrant / someone who had left into someone who had arrived’. Joumaa’s work opens a portal to this experience. An experience that we might like to think belongs to the past, but its perpetual, perilous transitions persist today.

Joyce Joumaa’s installation Memory Contours is on view in Foreigners Everywhere, 60th Venice Biennale, through 24 November