The embattled island’s horror-comedy-Kungfu flicks reveal both a sense of humour and a statement of intent

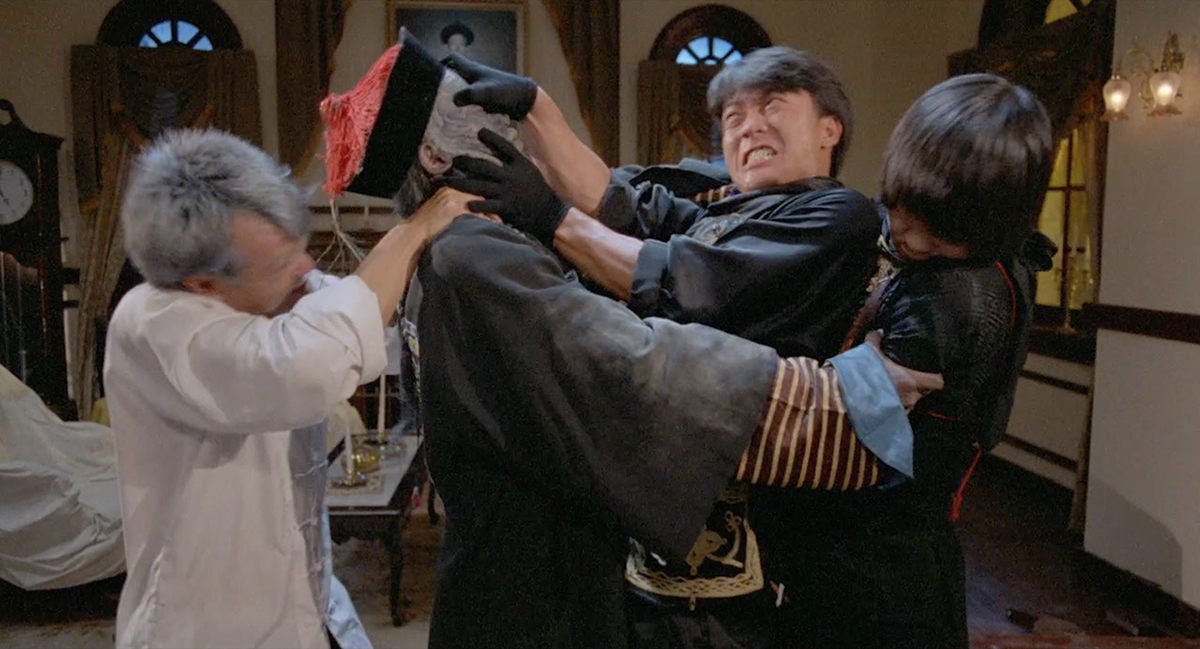

Mr. Vampire is a classic Hong Kong horror comedy set in Republican-era China. Released in 1985, it launched the career of director Ricky Lau, who by the early 1990s had produced four sequels, and sparked a slew of other similarly themed productions out of the then-British colony. In the opening scene, Man-choi, a student of Taoist priest Master Kau, lights a bundle of joss sticks inside a funeral home. “Dinner’s ready!” he shouts in Cantonese, and proceeds to offer it to a line of standing corpses dressed in the robes of Qing dynasty officials. The corpses, made compliant by paper talismans stuck to their foreheads, are ‘customers’ of another priest. The flame of an oil lamp flickers, the corpses quiver. Man-choi steadies the flame and they fall still. He turns to ‘feed’ other customers who are enclosed within coffins, jamming a few joss sticks into the joints of each traditional-style casket. One of the coffins spits out its incense. He pries open the lid and, to his horror, a pale hand shoots out and grasps at Man-choi, causing him to fall. Meanwhile his attacker jumps from the coffin and scuttles out of view. Man-choi grabs a bagua mirror from the wall and turns to see a vampire – its trademark snarl revealing its fangs, its hands raised and fingers curled into claws – that he attempts to ward off with the octagon-framed amulet. In the ensuing scuffle the oil lamp is knocked over and the talismans flutter from the standing corpses. Unnoticed, they begin to hop. As the vampire corners Man-choi, the soundtrack reaches a climax, his hands close around the student’s neck, he chomps down, and then… his teeth fall out. It’s Chau-sang. Master Kau’s other student. “Don’t be so scared,” he says, laughing. But the corpses close in.

The Hong Kong film industry has been responsible for its fair share of vampire movies, starting in 1936 with Yeung Kung-leung’s Midnight Vampire (just five years after Universal’s Dracula hit Hollywood as the first licensed cinematic adaptation of Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel). While The Legend of the Seven Golden Vampires (1972), coproduced by British horror specialists Hammer Film Productions and Hong Kong’s The Shaw Brothers, who popularised the Kungfu genre, was, according to its tagline, ‘The first martial arts horror spectacular ever filmed!’, it would take until the mid-1980s for the horror-comedy-Kungfu flick to become a standard of Hong Kong cinema. Directed by Lau and produced by Sammo Hung, Mr. Vampire (rereleased this year on Blu-ray) nods to Seven Golden Vampires and Encounters of the Spooky Kind (directed by Hung, 1980), blending Kungfu sequences with mo lei tau, a type of slapstick humour developed in Hong Kong film and TV during the 1970s.

In an instance of the latter, the main character of Encounters… is instructed to throw chicken eggs at the vampire to ward him off, but an egg-seller adds duck eggs to the basket, which fail to do the trick. In Mr. Vampire, Chau-sang is told to fetch lo mai (glutinous rice, which counteracts vampire venom), only for the rice-seller to spot a profit and cut the bag with ordinary rice. Such apotropaics, while used for comedic effect, also parody Western vampire films in which garlic is used to repel the creatures. While references to the protective qualities of garlic and other pungent ingredients can be traced back to ancient folk traditions and early-Abrahamic religions from around the world, the use of garlic was popularised by Stoker’s nineteenth-century Dracula, whose gaunt, pale and sexualised depiction would become canonical of the vampire genre. But these are not Western vampires. These are geongsi. Commonly translated as ‘Chinese hopping vampires’, but actually meaning ‘stiff corpses’, geongsi (jiangshi in Mandarin) are more akin to the revenants found in classical Chinese literature, most notably in Qing dynasty writer Pu Songling’s Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio (1740), a collection of supernatural tales. Indeed, it has been noted that Mr. Vampire takes inspiration from these stories, and perhaps more specifically from ‘The Resuscitated Corpse’, in which the corpse of a woman attacks a group of travellers, one of whom escapes by holding his breath so she can’t hear him breathe (an escape tactic also deployed by the characters in Mr. Vampire), and the tale of ‘Miss Lien-Hsiang’, which is mirrored in the side story of Chau-sang being seduced by a female ghost named Siu Juk (or Jade). The concept of reanimated corpses comes from the tradition of ‘corpse driving’. The population of China exploded during the Qing dynasty, between 1700 and 1850, growing from 150 to 450 million people, which, coupled with the geographical expansion of the empire, meant that people often worked and died far from their hometowns. Taoist priests would be charged with transporting the bodies back to their towns and villages, and so popular stories emerged that the priests would reanimate the corpses and, using talismans to control their movements, help them hop their way home.

That the geongsi costume adopted in Hong Kong cinema is derived from the Qing dynasty is less a reference to the era in which Pu Songling’s stories were written than a motif reflecting the anti-Qing sentiment that resulted in the overthrow of the dynasty in 1912 and the establishment of the Republic of China. Which also heralded the return to power of the Han Chinese. The Qing dynasty, established by the Manchurians of now northwestern China and known for its subjugation of the Han people, were considered oppressors. For the Republic (and later the People’s Republic of China), then, the geongsi represented a monstrous manifestation of that imperial rulership that consumed the spirit of its people. But the geongsi of Hong Kong cinema is a creature trapped in limbo, a hybrid stuck not just between two states – living and dead – but also metaphorically, with the Handover imminent, between two ideologies: that of the British Overseas Territory and the PRC.

While the reference to anti-Qing attitudes might have directly appealed to Mainland Chinese audiences (as it certainly did to Taiwanese fans), strict film censorship inaugurated during the Republic of China and continued by the PRC after 1949 meant that films produced on the Mainland that included supernatural and superstitious elements, as well as those in the wuxia genre (which depicted martial arts heroes of the flying kind, believed to instil rebellious instincts among audiences), were banned outside Hong Kong. One can’t help but consider whether the conflation of horror, Kungfu and comedy (particularly of the irreverent kind) in geongsi films reflected local sentiment during the decade in which Hong Kongers’ anxieties about the Handover, local identity and their future were sparked by Margaret Thatcher’s 1982 visit to discuss the reunification.

The geongsi genre hybridises Western vampire and Chinese revenant lore, hopping between the cultures by recalling the vampire’s popularity as a Western analogy for crisis (particularly in relation to plagues and epidemics, a reference that perhaps finds echoes in the current COVID-19 pandemic, which purportedly originated in bats) and Chinese practices of filial piety. Geongsi films, however, also make a habit of poking fun at tradition.

In Mr. Vampire, Master Kau meets with Mr. Yam, a rich businessman who is looking to disinter his father and rebury him in a more auspicious plot in order to attract even more wealth to his family. Yam insists that the existing plot is a good one, but Master Kau deduces from the size of the grave that something might be wrong. “We’ll bury him the correct way,” he says, frowning, which then prompts some quick Cantonese wordplay wherein Man-choi sidles up to Kau, asking, “What’s the French way?” Kau rebukes him with something that roughly translates to “I’ll punish your head!” In another example of mo lei tau, puns are frequently employed in this film, but the nuances in tonal difference are lost in the subtitles. The coffin, it turns out, is buried vertically instead of laid flat. Bad burial equals bad vampire.

Geongsi films, as a hybridisation of cultures, occupied a specific position within the Hong Kong film industry’s history of forging its twentieth-century identity. Against the backdrop of its complex historical relationship with Britain and Mainland China, the genre was less about defining what was and is uniquely ‘Hong Kong’ (which appeared shortly after as romanticised and nostalgia-fuelled depictions in Wong Kar-wai’s dramas, produced on the cusp of reunification and thereafter) as it was about claiming autonomy over its mixed heritage. With tongue firmly in cheek. History, one might say, has a way of coming back to bite.

Mr. Vampire is being rereleased in July 2020 on Blu-ray, by Eureka Entertainment