A reencounter with the work of Fiona Banner prompts a reassessment of art institutions as political fields of hegemonic control

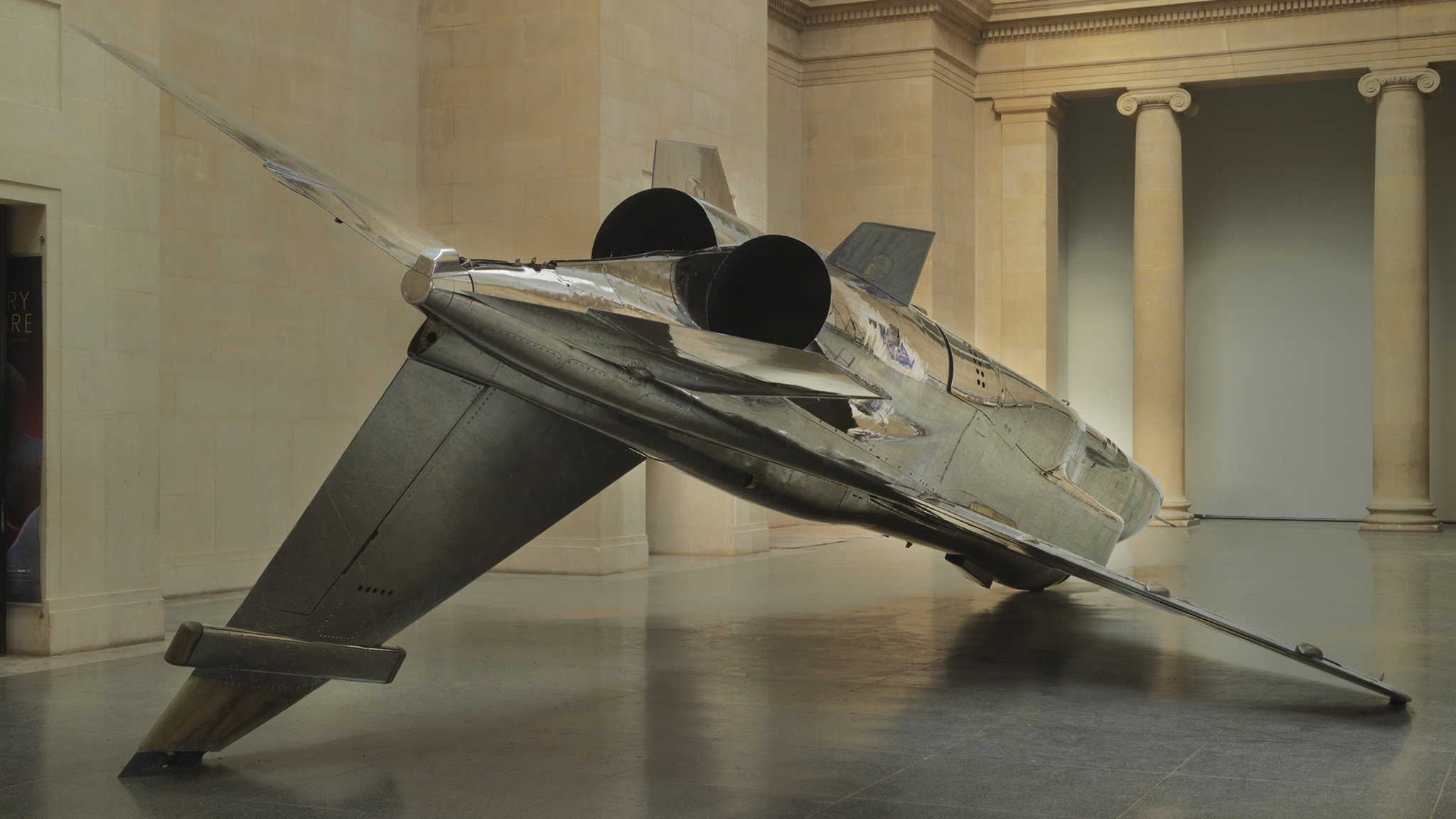

A few months ago, I was stood in the main hall of the Tate Britain in London talking to the artist Fiona Banner. It felt significant. My favourite use of that space had been an installation created by Banner over a decade earlier, in which she had hung a Sea Harrier from the ceiling and parked a Sepecat Jaguar on the gallery floor – two RAF planes that had been recently decommissioned. The installation was titled Harrier and Jaguar (2010) and at the time I remember reading that Banner, who is best known for her vast wordscapes comprising hand-typed or written sentiments, believed the objects represented the ‘opposite of language’.

Through the total oddity of their placing, and their enormous, undeniable presence in the otherwise civil and orderly gallery, Banner’s planes suggested the violence of Britain, the violence of Westminster just a few streets away, and perhaps the violence of art. Because, if we take the idea communicated by Edward Said, quoting William Blake in Culture and Imperialism (1993), that empire follows art, and not the other way around, then it is the other works in the Tate’s surrounding rooms, many of which were commissioned by the most powerful in their day, that really hold the key to the mentality of expansionism and hegemonic control.

Said was a professor of literature, and his work is a speculative challenge to the mythology of the western canon and the power structures that it protects. But this statement is also useful for helping us to assess the implicit contract that is drawn up between the art institution and public. Banner’s intervention transformed the gallery into a temporary aircraft hangar. It is a metaphor that has seemed increasingly appropriate in recent months: the ongoing brutal siege of Gaza – with Israel facing charges of genocide in the ICJ – has exposed the limitations of the international legal system and other instruments of Western imperialism, not to mention the limits of language, while also complicating the authorised forms of cultural expression that are held up by the latter as its apogee. Not only does the metaphor highlight art’s role in the formation of power, but more subtly, the somewhat bizarre and hollow function of the gallery in the modern western imagination. The recent censorship of pro-Palestinian voices has been routinely justified on the belief that galleries, and cultural institutions, should exist outside the scope of political concern and material reality – hangars after all, serve as peripheral holding facilities and semantic breakpoints in the life of an object, providing temporary respite and neutral framing for that which is devastatingly functional on the outside.

In January, artist Johanna Tagada Hoffbeck shared an email from a nameless German museum. It said that the museum was cancelling her show after she posted a Free Palestine badge on social media, on the basis that the museum ‘is actually a non-political field’. Following the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948, and the necessity of decolonisation, the museum and gallery were rhetorically reframed. What had once been sites of national or personal prowess, displaying the spoils of empire and stolen wealth, became supposed protectors of human ingenuity and achievement. Objects that belonged to different societies with their own trajectories of cultural expression and genius, were narrated through the flat, monocultural conception of human ‘progress’. The spoils of colonialism needed to become depoliticised artefacts of a somewhat distant past. Their baggage would then be offset by the acquisition of new works that dealt in more progressive subject matter.

Yet even without acknowledging the flaws in that post-war, post-historical mindset, the institution has undermined its own authority by failing to recently uphold even the most basic core tenets. Namely: freedom, dignity and the right to expression. Instead, ideas considered for inclusion in the gallery must necessarily be considered decommissioned ideas, their wires safely cut. An image used by the artist Hito Steyerl in the opening of her book, Duty Free Art (2017), illustrates this mentality. In the year that book was published, a Soviet battle tank had been driven off a Second World War memorial pedestal in the town of Konstantinovka in eastern Ukraine. It had been seized by pro-Russian separatists utilising every possible means of assault, in what might be considered a story of enterprising imperialists on the one hand, and on the other, a strange fable about the lability of the artefact, the pedestal and the past more broadly. ‘One might think that the active historical role of a tank would be over once it became part of a historical display,’ writes Steyerl. ‘But this pedestal seems to have acted as temporary storage from which the tank could be redeployed directly into battle.’ This recalls another story, about an artefact that was not deployed in battle, but invoked by law: an assault rifle, which was removed from its cabinet at the Imperial War Museum in London in 2015, after it was discovered to be the murder weapon used to kill five Catholic people in Belfast in 1992.

The storage unit generally exists outside the scope of human activity. And yet, from tools of propaganda to items looted in campaigns of cultural impoverishment and psychological tyranny, munition and even possible evidence, much of what the gallery contains has a possible political and functional life beyond its four walls. It is the inability to ever reconcile these two realities – the rejection by the former of a material reality that can only be denied for so long – which has caused the curatorial paralysis and embarrassment that we have witnessed in recent months. For example, one suspects that the Zabludowicz collection, which recently closed its doors in London, was able to exist for as long as it did partly on the basis that its material conditions, namely the allegations that its profits were being used to fund Israeli military equipment, were a parochial distraction from the subject of art. Likewise, when the Arnolfini in Bristol, which cancelled a Palestinian film event in November last year, issued an apology expressing ‘deep regret for the distress caused to those we consider allies’, it sadly only demonstrated the virtual nature of so much contemporary art speak.

There are countless other examples, of artists whose ideas were permitted in the safe and hypothetical space of a world in relative peacetime, being dismissed when warfare determines that their ideas hold currency. Among many others is the story of Samia Halaby and Candice Breitz, two artists whose exhibitions were cancelled on account of their support for the Palestinian people, by Indiana University and The Saarland Museum’s Modern Gallery respectively, as well as the withdrawal of the Hannah Arendt prize from Jewish writer Masha Gessen.

Gessen was criticised for an article that they wrote for The New Yorker, claiming that German guilt towards the horrors of the Second World War was being instrumentalised to discriminate against Muslim people in the present. The counterargument to Gessen’s article hinged on the Holocaust being a discrete episode in history, a genocidal campaign that might never be replicated or recur in another context and against another people. That tendency, to refute the continuous nature of history, is another barrier to language. It prevents the possibility for dialogue. It says that these events are only to be considered in terms of memory, and beyond the scope of contemporary discussion: they must never happen again and so they must become unspeakable. The event is sealed behind glass, constituting a past that can be perused and pondered, but never considered a part of the present. To draw comparison between extreme current and past events would constitute a breach, a driving of the tank off its plinth; in doing this we refuse the reality of the event and its role in an ongoing human history.

The point has been made that it is hypocritical of galleries and museums who have previously hosted talks and exhibitions on the subject of decolonisation, to then censor those who have spoken out in support of the Palestinian people. But the mistake is believing that the institution in its current guise is even capable of such a feat, precisely because of that material denial. If empire does follows art, then it stands to reason that in a neoliberal society, the established galleries or museums will only operate at the level of representation, abstracted capital and ‘ideas’.

That objects be considered symbolic routes to guilt or remembrance, or, conversely, inspiration, in the mind of the viewer – and every exhibition wall text seems to suggest that they must – is a mirroring of the colonial mentality. Without any attempt to situate the significance of the object in struggle or systems of power that remain and have persisted for centuries, is a way of denying their agency and of rendering the past, if we’re dealing in artefacts, a ‘foreign country’, to use the words of England’s very own L. P. Hartley.

Harrier and Jaguar was important to me at the time, but what Banner told me that evening in the Tate Britain had implications for the definition of art, its role in empire, and the possible function of the gallery. At the time of the exhibition, there had been some commercial interest in the two planes, and for the first time in her career, Banner looked set to get rich. But when the call came from the interested parties, she had the unfortunate task of having to explain that the planes had been melted down. Two enormous fighter jets, as long and as tall as the main hall of the Tate Britain, had been reduced by Banner into a pile of ingots gathering dust in the corner of her studio.

This act was surely instructive to the former colonial power, but Banner had also done something radical in terms of reviving materialism. In possessing these objects of war, she understood that her job did not end with the closing of the show, but that when faced with the unspeakable, a necessary transformation of reality was also required. The act of exhibiting had been transformative. The gallery had played a role beyond mere display purposes, prompting the artist into direct action. After Gaza, there can be no other definition: enter the terrain of real people and present struggle, or submit to the irrelevance of a decrepit empire in its final throes.

Nathalie Olah is the author of Bad Taste (2023), Class (2021) and Steal As Much As You Can (2019).