A play by Olivia Erlanger at London’s ICA returns to the schools of philosophy that tried to decentre human subjectivity – and features horny, talking shower-heads

After recently seeing a performance of Humour in the Water Coolant at the ICA, a play written by the artist Olivia Erlanger, I found myself wanting to reread a favourite book of mine from recent years. ‘I live, the way numbers live, and the stars; the way tanned hide ripped from the belly of an animal lives, and nylon rope; the way any object lives, in communion with another,’ reads a passage from The Employees: A Workplace Novel of the 22nd Century (2018) by Olga Ravn. It is a novel that forms part of a tradition in both art and literature that is liberated from, but also deeply indebted to, two philosophical schools of the late 2000s and early 2010s: speculative realism and, its subset in particular, object-oriented ontology. A crash course: both schools tried to decentre human subjectivity from philosophical thought and reanimate discussion about things and our relationship to them. Broadly speaking, they considered it a folly of the post-Kantian world that we attribute supremacy to human perception and experience.

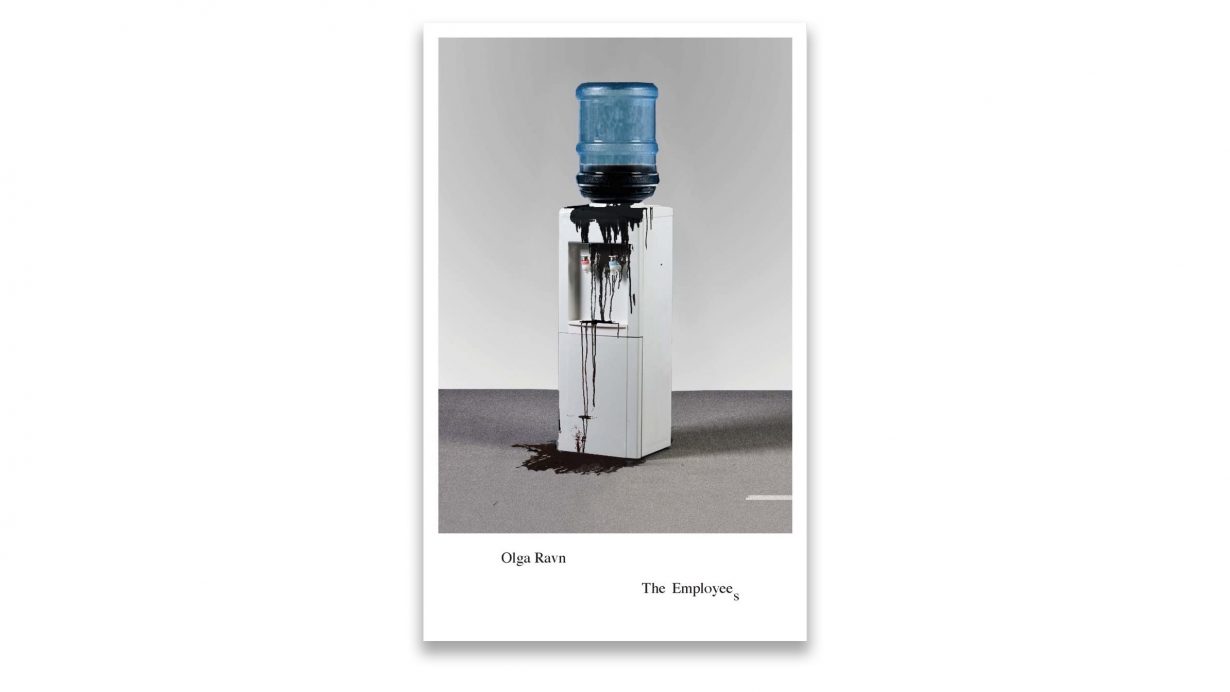

In this vein, Ravn’s book details a fictional scenario in the near future in which both humans and humanoids are forced to live on a ship that is travelling through space. When the vessel acquires a variety of strange alien objects, both demographics start to develop complex feelings that call into question the nature of being. One edition of the novel, published by New Directions, features on its cover a water coolant overspilling black liquid. Given Humour… is a play about a woman ‘haunted by the appliances in her home’, and features a water coolant in its title, a comparison of the two – or at least a reading of one in the context of the other – was only natural.

Originally conceived for Kunstverein Gartenhaus in Vienna as part of Erlanger’s exhibition Appliance (2022), Humour… has attracted attention both for its subject matter and Erlanger’s burgeoning reputation as a chronicler of late capitalist fatigue, particularly in relation to the lives of present-day US citizens. The play hinges on main character Sophie (Honor Swinton Byrne) hiring the services of a medium called Crystal (Michelle Newell) to conduct a séance. Through this act, each appliance in the home, here personified by an actor – Lamp (Callie Hernandez), Oven (Amie Francis), Shower (Dani Moseley) and Fridge (Adrian Pang) – delivers a monologue that expresses, in one form or another, a fear of becoming obsolete. A lovelorn shower yearns to fuck Sophie but mourns the fact that the feeling might not be mutual, an oven laments its build-up of grease, while a frustrated lamp wishes only to demonstrate the full breadth of its sexual charisma by being turned on occasionally (instead, it’s always the overhead light that is used). One highlight is a monologue delivered by the fridge, in which it rails against the emergence of a generation that favours external experiences over home comforts and modern conveniences, and mocks Sophie’s ineptitude as an amateur chef — she is always failing to use the sauces that she makes and stores by the batch.

In isolation, Humour… is – as billed – funny and observant of modern domesticity. But art is a discursive discipline. Having fallen out of favour in philosophy departments, object-oriented ontology became fashionable in art and literature, where it also ran the risk of becoming unmoored from its conceptual underpinnings. In a recent interview with Verso, climate activist and professor of human ecology Andreas Malm illustrated the former, summarising the feeling of a great many in philosophy and humanities departments, when he described the discipline as “bullshit”, claiming it had no relevance to anyone outside of very “particular kinds of academia”. I do not share Malm’s view necessarily. However, I do believe that regardless of personal beliefs, work created in the tradition of object-oriented ontology needs to be assessed according to its fidelity, and contribution to, that tradition.

The best work, then, is that which respectfully engages with the primary texts of Bruno Latour, for example. At first, I wondered if the absence of this literature was an ironic turn; if the coincidence between the title and the cover of Ravn’s book wasn’t a coincidence at all, but a deliberate attempt to undermine the author’s conformity to a school of philosophy that Erlanger rejects in her play. After all, objects here are not imbued with the ‘spirituality’ of Latour’s definition, or the cultural significance to make them “worthy of attention and respect,” but bit-parts in the life of the its central protagonist.

Sophie, who is largely housebound, depressed and overcome by the personal responsibility of having to maintain a home, develops an understanding of her reciprocity with the objects, realising how taking greater care of them might also lead to taking greater care of herself, resulting in a less burdensome existence. If there is an admirable attempt to highlight the interdependency between human and object, there are also far too many normative assumptions in the story’s telling. The impetus is always towards self-improvement and wellness – a fact that is capped off by the medium leading the séance, who issues a word of advice to open the windows from time to time and perhaps light a candle. The object relationship is also viewed through a lens of emotion and yearning that is divorced from wider material factors and labour: Sophie sits atop the objects and any sense of them being joined in a collective struggle is noticeably lacking.

Malm reduces object-oriented ontology to people who claim that a stone has agency, and that’s what we have here: a play in which the stuff of the home has been ventriloquised. By contrast, in Ravn’s novel there is no central, authorial voice or protagonist, and in a turn that flattens all such previous hierarchies, the story is told through several anonymous testimonies presented by humans and humanoids alike. Canadian writer Camilla Grudova, working in a similar tradition, deploys a sentence-level refusal of logic, with reason breaking down in clauses that directly contradict each other, creating new, linguistic chimeras to accompany the monstrous formations that feature in her stories. This constitutes a queering of perception, urging us through the peculiarity of its being to consider the possibility that our literalisms might be lacking, as all good surrealist work should. Erlanger’s world, by contrast, is one that relies on the animating force of a séance to bring its objects ‘to life’; its objects share the same emotional landscape as the characters of a soap opera.

I make these points not to dunk on any individual artist, but to advocate for greater fidelity, which seems like a moral duty in the present climate. Performance alone is not the riposte to hypercommoditisation that we might think it is, particularly if those performances do not also challenge the commercial imperatives of entertainment. By no means am I against making work that speaks very directly and adapts philosophical concepts for a new audience. But perhaps now is a good moment to stress the difference between artworld-speak that is the product of institutional affiliation and initiation, and valid complexity. Erlanger’s play simplifies the ideas of many artists working over many decades and, in so doing, erases them. The charge of elitism is rightly made against modish styles aimed at speaking to a tiny minority of people, all of whom are armed with identical schooling, but a worldview that challenges the assumptions of Kant and the Enlightenment is – by its very nature – never going to feel ‘easy’. We can dismiss the enterprise altogether, in the way of Malm. Or, if we are going to give credence to a belief that attributes many social and ecological ills to the supremacy of human-centred perception, we must also be prepared to swim in water that is much stranger and more unsettling than that of Erlanger’s creation.

Nathalie Olah is the author of Bad Taste (2023), Class (2021) and Steal As Much As You Can (2019).