Before the pandemic, another kind of travel ban was implemented in the US. At the end of 2017, President Trump’s Executive Order 13780 prohibited entry to nationals of Iran, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria and Yemen on the basis of protecting the US against extremist terrorism. Though this was to last 90 days, a further proclamation extended the ban indefinitely. By 2020 varying degrees of prohibition covered nationals from North Korea, Chad, Venezuela, Eritrea, Kyrgyzstan, Myanmar, Nigeria and Tanzania. Some of those not permitted to enter the US were those who already held Diversity Immigrant Visas (also known as the Green Card Lottery visas). The ban, which critics called out as anti-Muslim, was revoked in 2021.

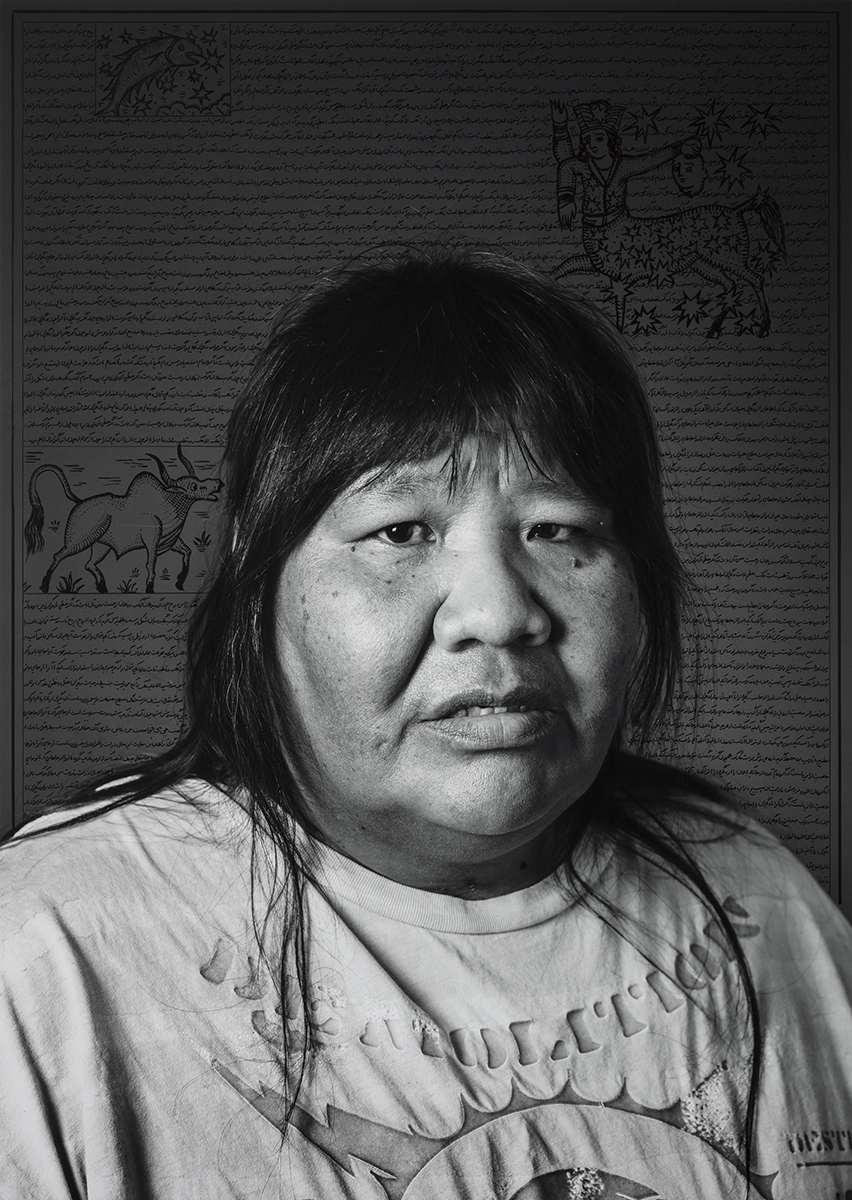

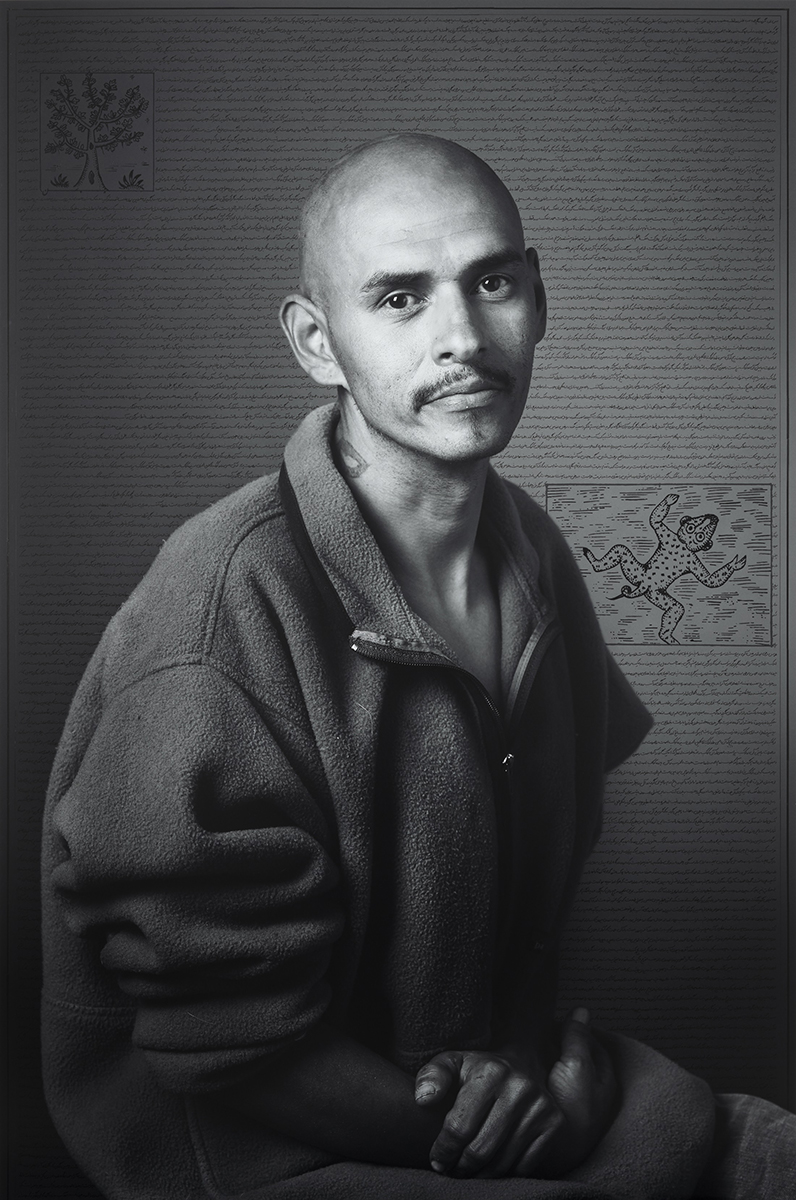

Somewhere between these two points in time, Iranian-American artist Shirin Neshat began working on a group of works collectively titled Land of Dreams (2019–), comprising 111 black-and-white portraits, a black-and-white two-channel video and a feature film shot in colour (these last following a central character named Simin). Each of these might be looked at, or watched, separately – but they are also jigsaw pieces that, when fitted together, form a bigger picture. Neshat’s early photoworks (Unveiling, 1993, and Women of Allah, 1993–97) and videos (Turbulent, 1998, Rapture, 1999, Soliloquy, 1999, and Women Without Men, 2009) focused on providing a critical voice against the sociopolitical impacts of Islamic law on women in Iran and are informed by the artist’s experiences of returning to a home much-changed since the Iranian Revolution in 1979 (following an encounter with law enforcement officials in 1997, she has not returned). Always semiautobiographical, those early works of Neshat’s mostly reflected on her Iranian heritage alone. This latest body of work, however, might be the most representative of her status as an “American immigrant”, as she says, a position she has long held but never quite explored. In Land of Dreams she turns her lens towards what it is to live in the US as someone who is not white. Where the idea of those titular dreams (of success, money, a better life) are sold to the many, but granted to few.

In the videowork and feature film (the latter premiered at Venice Film Festival this past September), Simin is a ‘dream catcher’. She is also Iranian-American. In the video she works for a secret Iranian organisation stationed in a bunker, but in the film she is an employee of the US government (for whom, at one point, she is asked to spy on a reclusive Iranian colony). Based in New Mexico, she travels to different households on assignment to collect the most recent dreams of their occupants. Most of the time, they are willing to tell her. Sometimes they’re not. When she likes a dream, Simin asks if she can take the subject’s portrait. She goes back to a motel room, dresses up as the person, switches on a webcam and recounts the dream in Farsi to an anonymous audience. By association, Simin is also the photographer of the pictures that make up Neshat’s Land of Dreams portraits – each featuring a handwritten background of Farsi-translated dreams. Along her journey, Simin is met with a mixture of suspicion and curiosity, finding herself straddling two different identities, never quite accepted by either her Iranian audience or by the country in which she was raised.

The release of a feature film that highlights themes including immigration, belonging, racism, trauma and surveillance brings into focus what Neshat has been attempting to build for nearly four years: a world – or land – in which a critique of white American values, prejudices and the American Dream is reflected in its own constructed and absurd nature. Speaking to Neshat, it’s sometimes hard to know whether she’s talking about Simin or herself.

ArtReview Asia Land of Dreams (2019–21) includes portraits of real people that you yourself interviewed, some of whom appear in the video and film, together with their photographs, which it is implied have been made by the protagonist Simin. What are we to make of this slipping between worlds – or ‘lands’?

Shirin Neshat It was a real experiment for me because I used to keep everything separate: the photography from the video, the video from the movie. The beginning of that experiment was to photograph people in New Mexico and introduce myself as an Iranian citizen before asking them to share their dreams with me.

It was about trying to relate to people from different backgrounds, whether they were Native Americans, Hispanics, African Americans or white Americans. Trying to create this human bond between an outsider and insider through this idea of living in America, living in the land of dreams, sharing our dreams and nightmares. Then came the video, in which this fictional character of Simin became a sort of alter ego of mine, who goes to these households and takes pictures of the residents. In the video there is a different kind of fictionalised Iranian colony compared to what’s shown in the movie. In the movie, the American government plays a sinister role. I think that there is a thread of continuity in all three mediums: that is the Iranian woman living in America in exile. She is a photographer and she is after people’s dreams.

I also had this question: how can we take this theme and make it communicate different ideas to different audiences through different artistic languages? The art of photography, calligraphy, the direct gaze of the sitters, the video and the enigmatic and poetic relationship between the two worlds. The movie is still fresh, and not many people who have seen the movie have any idea that there is an artwork that comes with it, and people who have seen the artwork might have no idea there is a film.

ARA That’s a sort of act of translation then – or interpretation, which is maybe a more pertinent term in relation to dreams. This also relates to the idea of revealing and withholding (some of the characters in both the Land of Dreams video and film are willing to tell their dreams, while others are not). Is this withholding important to you?

SN It’s related to the culture of Iran. I often refer to the veil as an architectural emblem. I don’t like to generalise, but in the Islamic world we like to build walls around us. Things that we want to share and things that we want to keep private. In previous work, I think the veil for me is really symbolic of a male dominated society, the way that veils create barriers between what is personal and what is public, and what can or cannot be shared. What was the word that you used?

ARA Withholding.

SN Withholding. It’s exactly that. Ironically, on the other hand, I find the veil interesting in the way that it can give a lot of power to women, because as much as you have to conceal your body, you could also use the veil in an extremely erotic manner. The eye contact, the slightest exposure of the skin, becomes very erotic in a way that a naked woman on a beach isn’t.

The idea of temptation and sexual provocation within the parameters of these boundaries becomes very pointed. To me it’s about how over the course of history, especially within Iranian culture, we’ve been repressing so much due to censorship, lack of freedom of expression, dictatorship, and yet we always find ways of being vocal and saying everything we want to say.

That’s really what my work is about. For example, even in the video Turbulent, Sussan Deyhim is not supposed to sing, but then she sings a song that has no ties to a specific language and it’s so guttural. It’s really about revolting against all the codes. I think that ties into how I feel about the state of feminism in Iran: how women, ultimately, can still be rebellious within all the boundaries that they’re dealing with.

ARA In the West, Iranian women are often perceived to be oppressed and without any power to express themselves.

SN Many people in the West don’t understand. It’s difficult, this question of translation of ideas and cultures from one to the other. It’s almost like you fail all the time. I still have a lot of stereotypical readings of my work, which is pretty frustrating after all these years, because from my point of view I’ve always tried to show that women are constantly rebellious, defiant or breaking the rules. A lot of people look at work like Women of Allah [1993–97] and say they feel sorry. They think that I’m reiterating the oppression.

The subjects [women, violence, defiance] that I’ve chosen for my work, they really are exposed to different kinds of interpretations depending on who is looking at the work, where they come from, what their relationship is to art and conceptual art. A lot of people in Iran also misunderstand it. They think that I’m just trying to sensationalise some of these issues to bring attention to myself, but that’s older work. I don’t work with the veil anymore. I don’t make work about the revolution. I’ve moved on.

ARA Translation is still very much part of your work. Farsi is a recurring feature – from early photoworks in Women of Allah to the Land of Dreams project. In the latter photo series, though, the script is behind the subject, rather than written onto the body. And again, there is a degree of withholding, from those who can’t read Farsi.

SN The fact is any Iranian would know the meaning of the text. But I’ve lived longer in the US than I’ve lived in Iran, and although my work goes back to my Iranian roots, it’s never meant to stay only within that culture or that regional discourse. So the relationship a Western audience would have with a text they don’t understand is still as valuable. In the Land of Dreams photographs, what is written behind the subjects are interpretations of the subjects’ dreams. These

are original texts and illustrations, but that tradition goes back to a very ancient book of dream interpretations [Khab-gozari, c. twelfth century] from Persian culture. Although they might begin with and constitute a very ethnically specific source, they transcend those issues of locality, the cultural specificities.

Beyond that, the works also incorporate the idea of paradox: black-and-white film, male and female, natural and urban environment, mysticism and poetry, violence and politics.

ARA What is it about the idea of dualities that you’re drawn to?

SN I don’t see anything in any form of absolute. On a personal level, I’m full of dichotomies and feel conflicted by the parts of me that I like and respect, and the parts I absolutely hate, which I find demonic. I find that I’m always working against my own evils – the selfishness, the egotism, the narcissism, all of that stuff. But it’s also about making friends with those strengths and vulnerabilities. And then I’m a person who lives between East and West. I’m emotionally Iranian, but my character is very American, very Western. I’m always serving two audiences.

ARA How is that duality reflected in the character of Simin in Land of Dreams?

SN The whole film is about this Iranian woman mediating between her Iranian past and the American culture she was raised in. But it is also about mediating between her interior life and external life, and dream versus reality. There’s a lot to do with crossing boundaries. Simin is a very strange character who doesn’t really belong here or there. For me, it was an interesting idea to develop. For example, her relationship to the Iranian community is only through social media, where she uploads videos of herself, but social media also furthers this distance. If you speak Farsi, you will understand that she has an accent, so she’s not really fluent in the language. But she’s also not quite American.

While Simin is dealing with her interior world, she is also confronted by the expectations of other people. For me, this duality is about being in between, and then having to translate that idea for others through a work of art. Iranian people don’t understand my work so much because it’s so conceptual. Then American people don’t quite understand it for its cultural specificities. There’s always something lost in translation.

ARA But those gaps in understanding also add another dimension: a sort of mystery. Is this a case of something gained?

SN In the video, the mystery doesn’t lie only with the main character, but with the whole thing – in its bizarreness and absurdity. With the feature film, I feel that most of the mystery lies with who Simin is as a character. It’s difficult to figure her out. What are her intentions?

What are the reasons she does certain things? Why does she get a job at the Census Bureau collecting dreams? What is her ulterior motive? The mystery unravels itself and then at the end there is some kind of conclusion, but still, the intention was to create a character that is really hard to read. In other words, she doesn’t show many emotions and she holds something back all the time.

ARA So why dreams? What is it that draws you to them?

SN Dreams are so telling. They’re just so powerful. First of all, I have to say, I’m really interested in the work of Man Ray, Maya Deren and Jean Cocteau. All this surrealism, it’s so beautiful the way fictions unravel when you have one foot in reality and one foot in illusions. It’s wonderful to put a film in front of people where nothing makes sense. Then the people begin to realise that in their own dreams nothing makes sense. Often, as artists, we worry too much about things making sense. I like the unbelievability of poetry and dreams.

Dreams are truly a reflection of our subconscious. Our subconscious is so inundated with our anxieties, our fears and our desires. Maybe, in the end, the way Simin relates to human beings is in their subconscious mind, because she herself has so many fears and anxieties.

For a woman who never really fits into society, relating to people through their dreams made a lot of sense. I had a brother who unfortunately died young. I always felt that he was a person who never quite felt comfortable in the world. There are people who have a really hard time fitting in. In this case, art or creative imagination or impersonating someone else can help you to find a way of coping with your inability to cope with reality.

ARA Do you think this relates to the concept of the American Dream, and fitting in?

SN That was another layer of the intention behind the film. It not only follows the journey of this single woman and her obsession with dreams, but it is also a parody about America. The more political side of Land of Dreams is about identity, and how that identity is being compromised, and the more demonic image of a country that once was something. It’s a little bit like all of my work, because while it is very personal, it always has a leg in the political.

With the Land of Dreams movie, the intention was that while we are following the life of this woman who’s haunted by these two worlds – Iran and US, dream and reality – we are also really understanding the malice of a society that is spying on people’s subconscious for whatever selfish reasons. There is definitely a question of collecting data on people, but also there’s a lot of references to racism, bigotry, political injustice, poverty.

Every household that we chose to depict represents an aspect of American society. These were all really carefully worked on as self-contained ‘stories’ outside of Simin’s world. With the artwork [the video], those moments were much more about the people Simin visits, and she’s more like a bystander; they are like little poems. But with the movie, we had the opportunity to build all those layers, where each visit to a household was like a short story. I enjoyed developing that a lot because it was like six short stories, and then the main three characters moved in and out of them. As Simin travels through those stories, through other people’s dreams, she slowly transforms, and eventually, by the end of the movie, she is changed.

Shirin Neshat: Living in One Land, Dreaming in Another is on view at Pinakothek der Moderne, Munich, through 24 April

From the Winter 2021 issue of ArtReview Asia