The art scene in Thailand’s Isaan is building momentum through an emphasis on public participation in cultural production

A few years ago, Chiang Mai – the ancient yet cosmopolitan ‘rose’ of Thailand’s north – enjoyed its moment in the sun. For much of 2016, it was nigh on impossible to flick through the pages of an Asian inflight or travel magazine and not encounter a story praising this city’s ‘flourishing’ visual-arts scene. Driving this surge in interest – including a feature in this very magazine – was a new private museum, MAIIAM Contemporary Art Museum, that added a glittering, bricks-and-mortar destination to what had been, up to that point, a diffuse network of galleries and project spaces, many helmed by artists who live in and around the city. Its emergence hastened a neat, rise-of-the-underdog narrative – the overdue decentring of the Thai art scene away from the capital, Bangkok – that came bolstered by a genteel backstory: centuries of folk-craft heritage, as well as what ArtReview called ‘an organic though skittish history of nonprofit community projects’, meant Chiang Mai well deserved the hype.

Over the mountains to the east, however, a much scrappier story is playing out in Isaan: the Northeast. No world-class private museum is galvanising the local art scene. But what can be found in Thailand’s biggest geographic region – a largely flat and arid, rice-growing land of over 22 million people, many of them with stronger ethnic and linguistic ties to adjacent Laos than Central Thailand – is another decentring of sorts. In lieu of a rich gallery ecosystem, several artist- or activist-led events and platforms aimed at spurring new enquiry into microhistories and public participation in cultural production and political discourse have emerged. Also, a state biennale for Isaan is being cobbled together: on 11 June 2021, the postponed second edition of the roving Thailand Biennale, led by guest curator Yuko Hasegawa, is set to explore the institutional capital and ancient ruins of Korat, the region’s largest, gateway province.

What to make of it all? For leading Thai curator Gridthiya Gaweewong, the clusters of agonistic grassroots activity are, while belated, especially exciting, as they are bound up tightly with the region’s unique sociohistorical conditions. “In Chiang Mai, things are more aesthetic, community orientated, whereas in Isaan it’s more about the political collective and collectivism,” she explains. For decades, Isaan has been subject to lazy stereotyping – portrayed as either a simple land of somtum (green papaya salad), animist spirits, lao khao (rice whisky) and driving mor lam folk music, or a hotbed of grinding poverty and Communist or Red Shirt resistance – but these nascent initiatives and projects are, she adds, “showing us the other side: the intellectuals, the forward-thinking ideas” and “shattering the clichés of Isaan people as stupid, poor and in pain”.

These developments include The Isaan Record, a Thai-English language website founded in 2016 by a German journalist-anthropologist named Fabian Drahmoune. Spanning human rights, democracy, development issues, local politics and the arts, its reporting on the grassroots issues of the region is steady and unflinching. Recent contributions have included a long-form photo essay on villagers in Sakhon Nakhon province opposing a proposed potash mine, observations from a recent youth protest and an essay on state eradication of Tai Noi script, the written language of the ancient Lao Kingdom. Also notable is Noir Row Art Space, a gallery in the city of Udon Thani that recently staged an exhibition amid the monolithic radio masts and cracked structures of Ramasun Station, a former US Army intelligence base left to nature since the end of the Vietnam War. And then there’s the truculent art activism of Thanom Chapakdee: the bespectacled art curator-critic, born and raised in Isaan’s Sisaket province, agitating for an art scene that, in a nod to relational art and lusty revolutionary Marxism, unites and awakens.

Photo: Ekkalak Napthuesuk. Courtesy Jim Thompson Farm, Nakhon Ratchasima

This last development is particularly in-your-face. In Thai Art: Currencies of the Contemporary, art historian David Teh writes that culture itself, rarely armed revolt, has long been the core channel by which Isaan folk have resisted the state programme of ‘civilising’ the northeast that began under King Chulalongkorn (ruled 1868–1910). This resistance to what many from the region have long viewed as a form of creeping internal colonialism – a progress-led process that has pivoted upon the projection, by an often tone-deaf Bangkok, of a homogenising notion of kwampenthai (Thainess) and successive national development policies – can arguably be traced, to varying degrees, in the region’s old folk music, textiles and temple murals. Ditto the work of a few radical filmmakers (essential viewing: the Isan Film Group’s Tongpan, a social-realist docudrama exploring, through farmers’ eyes, the pernicious effects of inexorable modernity – banned in 1977, the year it was made, but now on the Kingdom’s official film heritage registry).

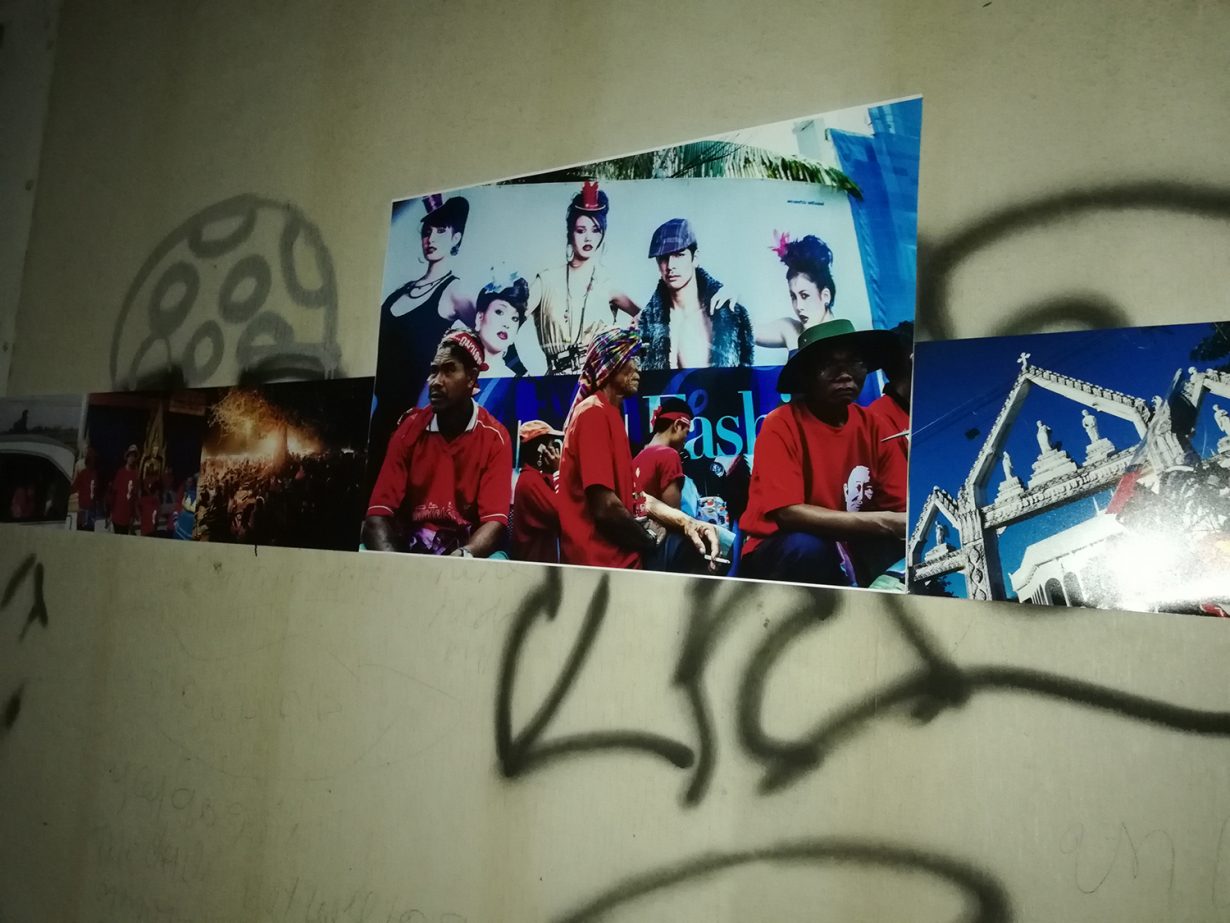

Chapakdee, however, has tried to up the ante with a combative strain of culture activism and urban interventions – a strategy that chimes with the pop culture-inspired protest art and social-media-driven guerrilla tactics of the country’s Free Youth movement (which is currently calling for Thailand’s parliament to be dissolved, state harassment ended and a new constitution minted). In October 2018 he launched Khon Kaen Manifesto: a three-week exhibition that railed against the myriad forms of social injustice inflicted on the Thai and Isaan people by authoritarian administrations old and new. And this former art professor set out his stall dramatically: he invited artists from the fringes to take part without limitations; he held the event in a spectral symbol of the 1997 Asian financial crisis (a derelict office building that was never finished); and he didn’t tell the local authorities his plans.

They showed up anyway, and promptly ordered him to cover up an artwork that placed Jatupat Boonpattararaksa, a leader of a student activist group who recently served a sentence for royal defamation, alongside other symbols of resistance and protest from modern history. But even if it hadn’t received the stamp of authoritarian disapproval, this three-week pop-up event would still have been deemed a success: it was well received in left-leaning quarters of the Thai media (including The Isaan Record: ‘The festival provided a rare acceptance in Thai art of democratic expression and countered a dominant discourse that condemns peripheral narratives as illegitimate and unworthy of respect’). Among the artworks was an event poster mocking the rhetoric of Field Marshal Sarit Thanarat, the infamous military dictator who, during the 1960s, used the city of Khon Kaen as the model-cum-launchpad for his vision of a developed, communist-free Isaan. Another was nothing more than a chair, hanging upside-down from a noose in an empty room – an elusive work by Nutdanai Jitbunjong that harked back to Thailand’s 6 October 1976 massacre, still a contested paroxysm today.

The abandoned building in which the first Khon Kaen Manifesto took place is now locked and empty, but Chapakdee is only just getting started. Perhaps the most symbolic moment vis-à-vis his desire for a paradigm shift in Thai art came on a nondescript Monday in June 2019, when he unveiled plans for The Manifesto by Maielie – a new art gallery that will also serve as a cultural exchange centre, a public forum for nonmainstream discussion and progressive points of view. Coming a few months after the government’s post-2014-coup ban on political gatherings had been lifted, this announcement was timed to coincide with the 87th anniversary of the Kingdom’s transition to a constitutional monarchy (24 June 1932).

“The people of Khon Kaen have always had a rebellious spirit, and we want to see more of it,” he told the small gathering, which included the then-leader of the recently dissolved Future Forward, Thanathorn Juangroongruangkit, and a fresh-out-of-prison Boonpattararaksa. Also present were the driving forces behind the MAIIAM Contemporary Art Museum back in Chiang Mai, Eric Bunnag Booth and his stepfather, Jean Michel Beurdeley, both avid patrons and collectors of contemporary Thai art. Much of the excitement at this event was directed towards a clear plastic plaque engraved with the words ‘Aesthetics of Resistance’ – a tribute to the small brass plaque that discreetly commemorated the 1932 revolution that led to the end of Thailand’s absolute monarchy, but disappeared, in mysterious circumstances, from Bangkok’s Royal Plaza in April 2017. A lost monument that one academic has called a ‘dark spot on the royal space’ was, here, reimagined and installed as the emblem of a new revolution – a source of hope in a disruptive civic space.

by Maielie gallery in Khon Kaen province. Courtesy Khon Kaen Manifesto

As of writing, The Manifesto by Maielie isn’t yet open. However, the planned dates for a new exhibition, UBON Agenda (21–30 November), and the second Khon Kaen Manifesto (10–20 December), point towards a slow, strategic building of steam, and also an urge to fan out into new urban contexts. The former will take place in an abandoned school in the built-up city centre of Ubon Ratchathani; the latter in a ‘smelly’ former brothel in downtown Khon Kaen. Artists are unconfirmed, but it seems likely that both exhibitions will be salons des refusés, consisting mainly of works by artists snubbed by the curatorial teams behind the forthcoming Bangkok Art Biennale and Thailand Biennale. Of his Khon Kaen outing, Chapakdee says: “This time we are expanding upon the idea of modernisers coming and making monuments.” Unperturbed by COVID-19, he adds that, once again, it will explore the genius loci of its venues – and fly under the radar. “We will just make an eruption,” he says with a low, conspiratorial laugh. “And, of course, there will be mor lam music.”

There is, undeniably, a partisan political element to these events, but Gaweewong, a close friend of his, believes its mechanics show how decentring should be done. “I like that Thanom is not focusing only on Khon Kaen,” she says. “I like the way he’s building and expanding and trying to use other provinces across Isaan not only as a site of artistic production, but also as a site for reinvestigating the history of each city, each province.”

Another rallying figure, she is well placed to comment on the merits of, and best methods for, shifting the power balance away from Bangkok. For well over a decade, the only steady source of well-researched exhibitions loosely concerning Isaan were the private institutions she works for: Bangkok’s Jim Thompson Art Center, where she serves as artistic director, and Korat’s Jim Thompson Farm, where her team guest-curates each winter. Although both on hiatus (the new building of the former is under construction, the latter will skip its December–January open season due to the pandemic), these closely linked institutions have, since 2003 and 2012 respectively, consistently sought to historicise and promote not just the region’s sericulture – the source of the Jim Thompson company’s lustrous silks – but also its vernacular traditions, rituals and forms.

In 2015, for example, multimedia exhibition Joyful Khaen, Joyful Dance reappraised mor lam music from a broad sociohistorical perspective, then went on to spur the creation of the Mobile Molam Bus Project, a melodic museum on wheels that has done laps of the local festival circuit. At Jim Thompson Farm’s Art on Farm season last December, visitors encountered a showcase of pa pawet, the long, delicate fabric scrolls that are painted with coarse takes on Buddhism’s Vessantara epic and paraded through villages during Isaan’s annual Bun Phra Wet festival. For Art on Farm, contemporary artists – Pratchaya Phinthong, Pinnaree Sanpitak, Mit Jai Inn and many others – have also been invited to make site-specific works addressing Isaan’s historical and cultural context.

On the face of it, the forthcoming Thailand Biennale aspires to such deep, long-term engagement. ‘The theme for this particular biennale’, the official announcement states, ‘is a proposal and a practice, primarily focusing on the ecologies specific to this region, in an attempt to create autonomous micro-ecologies.’ Hasegawa, the widely respected artistic director at Tokyo’s Museum of Contemporary Art, hopes to “bring out” the potential of Korat’s national parks, its ancient Khmer ruins (Phimai Historical Park), its silk villages, its city colleges and temples. And, speaking to ArtReview from Tokyo, she seems confident that something lasting can be created in spite of the many logistical hurdles thrown up by the pandemic. “It’s very important to create legacy,” she says. “Instead of projecting something, we are more focused on finding possibility, on highlighting forms of potential, on engendering something that already exists.” Permanent works are in the pipeline, as is lots of crossdisciplinary collaboration.

Gaweewong, however, is a bit sceptical. She worries that the placemaking she hopes to find in a biennale – the creation of a sustainable bottom-up legacy in the host community or city – will prove tricky to realise. “The problem is it’s really top-down,” she says, in reference to the Ministry of Culture department overseeing it, known as the Office of Contemporary Art and Culture. Also of concern is the peripatetic format – it doesn’t lend itself to cultivating relationships and meaningful engagement. “One of the producers of Setouchi Triennale once told me: if you want to do something right, you have to do it at least two times. The curators are going to have to work very hard to get into the history and ethics of each site.”

Ubon Ratchathani province, 2015. Photo: Teerasakchai Sirichana

Such misgivings are warranted – the first Thailand Biennale, in South Thailand’s Krabi province, was tainted by bureaucratic snafus and missteps. An artwork was removed on grounds of cultural sensitivity; others went unrealised; a bizarre televised opening ceremony made it look like an extravagant prop in a Geertzian theatre state. There is no discernible legacy to speak of.

Moreover, when it comes to appropriating the culture of Isaan, the Thai state arguably has form. Teh believes the shallow processes of affiliation and encompassment, part of what he has termed ‘a wider economy of appearances’, began in the nineteenth century with the photographing and collecting of ethnic costumes by Siam’s royal elite. More recent examples include the attempts to co-opt Loei province’s often bawdy Phi Ta Khon festival – when the unassuming streets of Dan Sai village are filled with ghoulish masks made from wicker and palm fronds, and palad khik (penis-shaped amulets) brandished – by a host of authorities, including the Tourism Authority of Thailand. Elsewhere, state-funded exhibitions such as the Bangkok Art & Culture Centre’s Isaan Contemporary Report (2018) have presented a Bangkok-centric vision of the region that, while acknowledging its dynamism, creativity, growth and history predating the nation, smoothed out – or omitted – the rough edges: the political discontentment, the animist practices, etc.

But while there is plenty of latitude for criticising the Thailand Biennale, could there also be room for excitement? Some observers believe that it is likely to produce some stimulating projects, largely on account of the number of Thai artists currently based in or actively exploring Isaan. At this point, it would be remiss not to mention Apichatpong Weerasethakul, who grew up in Khon Kaen and has routinely used Isaan – ‘The most precious treasure of all,’ he once said – as a source of inspiration and site of production for his features, short films and video installations. But past run-ins with the Thai culture ministry mean any involvement on his part is implausible. However, the talent pool is big, these days. Of late, there has been no shortage of Thai artists striving to find fresh angles on the region, particularly ones pertaining to its role in the Cold War. Not all are from Isaan. “A lot more artists from Bangkok and other areas want to explore what is going on – and went on – here,” says Gaweewong.

More Monsoon Songs Elsewhere (2018), by the Bangkok-born Dusadee Huntrakul, featured hyperrealistic drawings of ancient ceramics unearthed in Isaan by American archaeologists, then lost to a US museum. Through these drawings, he teased out the rarefied themes – neocolonialism, cultural restitution – dominating academic discourse about the discovery of Isaan’s lost Ban Chiang civilisation during the Vietnam War. Also shown at Bangkok’s 100 Tonson Gallery was Prateep Suthathongthai’s A Little Rich Country (2018): a series of small paintings replicating the covers of midcentury books, each one worn and faded after years of being used to promote or indoctrinate the region. Another still to have substantively grappled with Isaan is Korakrit Arunanondchai – during the research phase for his videowork No history in a room filled with people with funny names 5 (2019), he went to Udon Thani province in search of ‘naga portals’, a secret CIA black site, and folklore.

While the Thailand Biennale’s list of participating artists won’t be confirmed until the new year, the robust curatorial team headed by Hasegawa is also cause for early optimism. Well versed at navigating highly centralised art bureaucracies, she certainly won’t be fostering hyperlocal forms of counter-hegemonic dialogue, dissent and expression, as in the agonistic public interventions and democratic arena-making of Chapakdee: “I’m very polite when I enter somebody else’s land,” she says diplomatically. But she is determined to contribute meaningfully to Isaan’s recent stirrings. “I’m no pop-up curator,” she says. “I don’t like biennale exhibitions where, once everything is finished, nothing is left. Creating a cultural legacy for the people of Isaan is very important to me.”