‘I still see them sometimes, even now, the imagery stuck fast.’ On ‘Surfer’, and a century of potent mythmaking

You could say that such is the mythology of Guinness that a pint of the stout is to the Irish what steak frites is to the French. Or at least, that latter example was one that Roland Barthes wrote about in his 1957 collection of essays, Mythologies: ‘Being part of the nation, [steak frites] follows the index of patriotic values: it helps them to rise in wartime, it is the very flesh of the French soldier…’ (the rest of the book is about trying to decode the mythologies that are used to naturalise political and cultural ideologies).

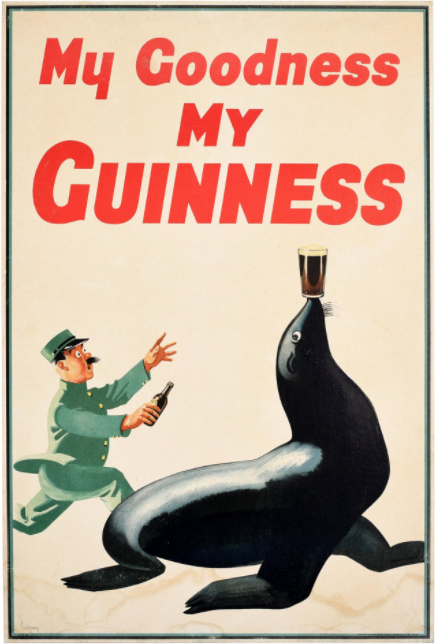

The Guinness mythology is due in part to memorable branding. At more than 250 years old, Guinness has spent the last century honing the aura surrounding its stout via its advertising campaigns, from its first tagline ‘Guinness is good for you’ (1929) to those iconic 1930s posters designed by John Gilroy depicting a feckless zookeeper trying to reclaim his precious pint from a collection of animals, to its awardwinning television adverts, some of which turned the 119.5-second pour-time to its advantage.

Take ‘Surfer’. It opens with a black-and- white closeup of a man’s face, brow furrowed; he’s looking up at something ominous-seeming. His eyes quiver, then blink. “He waits,” a male voiceover says, “It’s what he does. And I’ll tell you what…” The scene cuts to a group of surfers on a beach who grab their longboards and gallop into the sea. “Tick followed tock followed tick followed tock followed tick…” As the surfers disappear behind the crest of a huge swell, a bass riff looms out of the silence, and an aerial view captures the four of them, tiny, paddling out towards a big wave. A really big wave. Which they catch, and as they ride (“Ahab says, ‘I don’t care who you are, here’s to your dream’”), giant white horses rise out of the water, seafoam turning into solid muscle. “The old sailors return to the bar, ‘Here’s to you, Ahab!’, and the fat drummer hit the beat with all his heart…” One by one the surfers wipe out, tumble through the horses’ legs, vanish into the froth beneath trampling hooves. But one surfer, he bares his teeth in a snarl, stays low against his board, and gets barrelled in the curl of the wave. A horse crashes over, wild-eyed. And the surfer emerges. “… Here’s to waiting.”

That 1999 advert, directed by Jonathan Glazer and inspired by Polynesian surfers’ ability to read the ocean, Walter Crane’s 1892 painting Neptune’s Horses and Herman Melville’s fanatical Captain Ahab in Moby Dick (1851) (this last seeming an odd accompaniment, since Ahab is all revenge and bad vibes, and Guinness ain’t about that), brings together a trifecta of potent mythmaking ingredients.

I could probably tell you that watching ‘Surfer’ had an immediate and profound effect on my drink of choice. That in that moment, hypnotised by the anticipation of ‘the wait’, the romance and danger of the ocean as Polynesian surfer Rusty K skims through the tube of that really big wave, and Leftfield’s heartbeat-in-the- head soundtrack spliced from their 1999 song Phat Planet, I turned for a pint of the ‘Black Stuff’; watched the downward surge of bubbles like it was liquid sorcery; then had a slo-mo tastebud revelation from that first buttery sip on the tip of the tongue to the tang of the liquid as it slips down to the bitter-buds at the back where the flavour of roasted barley blooms; and never looked back. But I was eight. And tbh, didn’t even register the surfers (or the beer for that matter). Rather, I was just really amazed by these giant white horses crashing out of the waves, and so obsessed with them that I tried to draw them for months afterwards. And then for years after, I was conjuring those giant white horses during long, boring car journeys, watching them gallop alongside the road. I still see them sometimes, even now, the imagery stuck fast.

Back to that steak-frites-flesh thing: it brought up weird old memories of my nan insisting Guinness is “in the blood”, and then later learning that people really were given a free pint of Guinness for donating blood in Ireland (to ‘replenish’ lost iron). And then only while writing this, thinking about how she, an immigrant to the UK, might have said that sort of thing because she felt closer to home with a Guinness in hand, the same way a lot of people who are part of a diaspora feel connected to their ethnicities via familiar foods and drink. And the way in which the ‘patriotic value’ of Guinness is so habituated within the Irish psyche that its drinking has become synonymous with St Patrick’s Day; and as such, has done some denaturalising of its own by turning a Christian festival devoted to its patron saint into a (mostly) secular holiday that’s celebrated around the world. Maybe those giant white horses did have the desired advertising effect on me, or maybe it was just that the stout was as normalised a beverage in our household as tea and coffee, but if there was ever a cultural ideology to buy in to, sign me up! Because Guinness, after all, is good for you. Sláinte.