Skuja Braden, Selling Water by the River

Latvian Pavilion

You know all those bizarre, abject and unsettling thoughts you try so very hard to stuff into the furthest corner of your mind? So as not to give anyone an inkling of how truly disturbed you are? You know the ones. Well, they all seem to have splurged out at Selling Water by the River, materialising as surreal painted porcelain sculptures sprawled across the Latvian Pavilion, perched haphazardly on long white tables, sitting on the floor and mounted on the walls. Different domestic areas are vaguely recognisable because of the forms the ceramics take: there’s a sort of ‘kitchen’ section where plates depict body parts, a wall lined with vessels in the shapes of pairs of boobs decorated with jewellery or ‘tattooed’ with images of animals and words like ‘Tiger Milk’ and ‘12% MORE FAT’, food-shaped porcelain crawling with giant bulbous-eyed mosquitos, and serving bowls propped up by unidentifiable ceramic creatures eating one another in a kind of ouroboros fashion; a ‘dining room’ laid out with more crockery-like sculptures that have eerie, leering and grotesque faces; and a ‘bedroom’ with decorative ornaments inspired by Buddhist imagery and a ceramic bedspread installed vertically against a wall from which a pondscape seems to be leaking out – lily pads and aquatic creatures spreading everywhere. Among all these are many, many porcelain eyes, staring out from containers, vases, jars, even seemingly erupting out of the ground in organic blobs of eyebally mass; there are a lot of genitals – spiky-haired vaginas and anemone-like penis sculptures and more penises crucified, the gonads split apart.

Madjare. © and courtesy the artists

Judging by the convoluted exhibition text that accompanies Skuja Braden’s (Ingūna Skuja and Melissa D. Braden) installation, it’s unclear whether this was the effect they were going for. The meandering text draws on Zen Buddhism, bodies of water and borders, hospitality, LGBTQIA+ identity, Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro’s experimental performance space Womanhouse (1971), 1930s German kitchen design, private space, the body, gender equality in the Soviet Union, sexuality, the role of ceramics in modern and contemporary art and the ‘global circulation of water’. My advice? Just enjoy the disorientating madness.

and Milford Galleries, Aotearoa New Zealand

Yuki Kihara, Paradise Camp

New Zealand Pavilion

“Gauguin wanted us to be born with breasts while still having tipo,” says Dora, “I think that’s what he wanted – he is in love with the tipo”. Dora and her four fellow panellists nod at each other in a coyly conspiratorial manner. They are the stars of Yuki Kihara’s five-part episodic talk show First Impressions: Paul Gauguin (2018); they are also prominent members of Sāmoa’s Fa’afafine community who identify as third gender or nonbinary, and who are each invited by panel moderator Anastasia Fantasia Vancouver Stanley (aka Queen Hera) to voice their opinions on and interpretations of a series of the French Post-Impressionist’s Tahiti paintings.

Galleries, Aotearoa New Zealand

Kihara’s exhibition Paradise Camp (2022) unlearns Gauguin’s contribution to European art history by interrogating Pacific colonialism through an intersectional reframing that incorporates gender identity and climate crisis, presented through archival research materials and a series of photographs (Paradise Camp, 2020) that reinterpret Gauguin’s paintings. These are accompanied by the aforementioned episode of First Impressions which focuses on the painting Deux femmes tahitiennes (Two Tahitian Women, 1899), which plays on a large projector screen that hangs in the middle of the space. During the episode, they discuss the formal qualities of the painting, speculate on the motivations behind Gauguin’s desire to paint Tahitian communities and consider the context in which the subjects are being depicted from a Pasifika perspective. Despite dealing with more serious underlying themes like the exoticisation and objectification of Tahitian bodies and the role Gauguin played in France’s colonial destiny, the Fa’afafine panellists’ candid responses to the painting are light and humorous; and in this way, they are also able to poke fun at Western colonialist impressions of Polynesian societies. When Hera asks Dora, “What is a ‘tipo’?”, Dora replies bluntly, “a cock.”

Diplomazija Astuta

Malta Pavilion

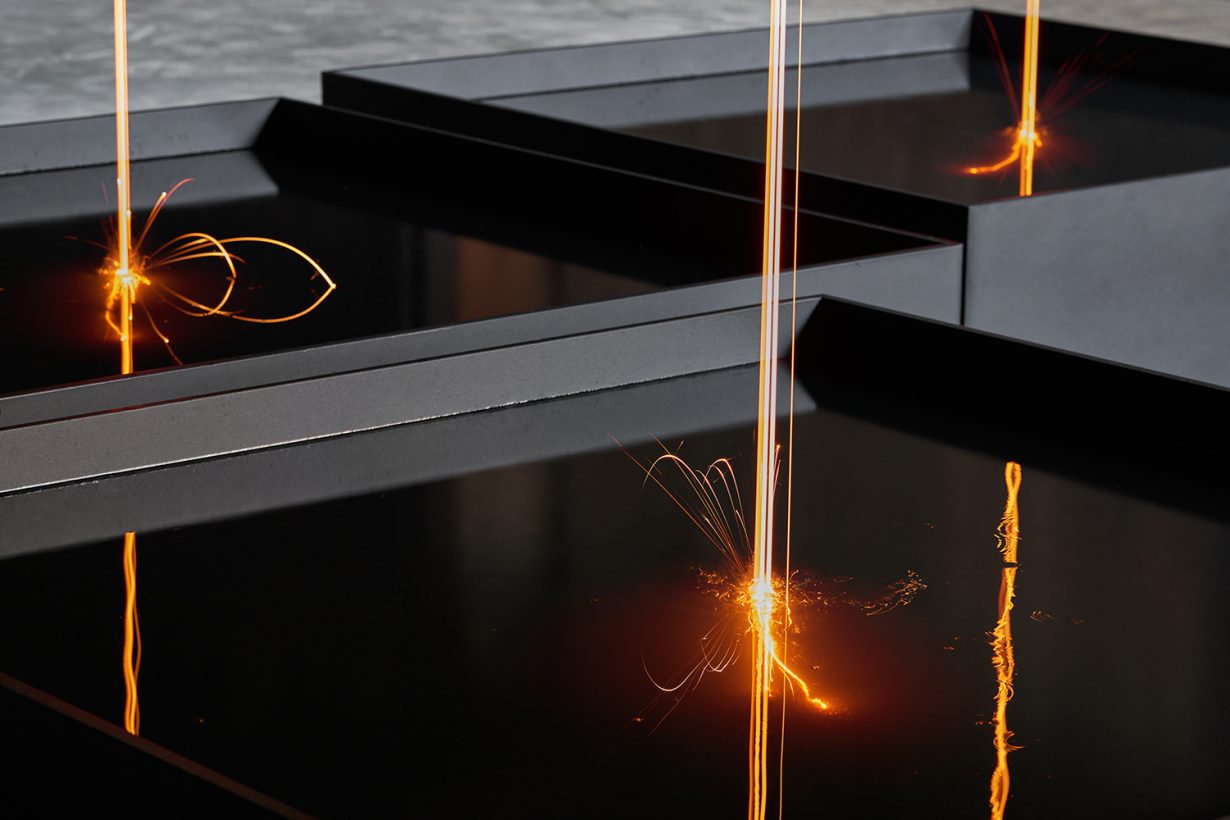

For a more meditative moment (read: a respite from the chaos of the biennale), head for Diplomazija Astuta. A reworking of Caravaggio’s The Beheading of Saint John the Baptist (1608) – which is housed in the Oratory of St. John’s Co-Cathedral in Valleta – the dimly-lit monumental installation is a collaboration between artists Arcangelo Sassolino, Giuseppe Schembri Bonaci and composer Brian Schembri. Sassolino’s blank blackened steel plate that measures the exact dimensions of The Beheading is installed at the far end of the cavernous space (the other side of which presents Schembri Bonaci’s Metal and Silence, 2022, a scrawl of text that combines Hebrew, Greek, Latin and Aramaic texts from religious writings carved into the metal). In front of the monumental ‘canvas’ are seven raised square pools of water that mirror the positions of the painting’s subjects (John the Baptist, Salome, her assistant, the executioner, a jailer and two prisoners); from holes in the ceiling, drops of molten steel fall into each of the pools choreographed to Schembri’s score, which draws on nonsecular musical works such as the Gregorian chant ‘Ut queant laxis’ (a Latin hymn written in honour of John the Baptist). At times, the droplets of molten metal fall one at a time, brief specks of light in the darkened room; at other moments, they fall like raining fire, a shower of golden orange. Each drop that sinks into the water lights up the pool briefly, before its glow dies out signalling its return to solid form. Taken outside of the subject matter of the painting, there is something oddly comforting about the installation – the knowledge that even when there is a lengthy pause in the music, the droplets of metal will continue to fall; each bead of light a symbol of the possibility for fluidity and transformation.